Blockchain For Grown-Ups, Part 2: What's Real?

In the first installment in our new series on blockchain—Cutting Through the Hype—we took a critical look at the hype surrounding blockchain to see how much “there” is really there. Even though it’s not as much as the hype would have us believe, there’s still a lot we can do with it.

In this installment, we dive a little deeper into what blockchain does do, what it does not do, and what it will do … someday.

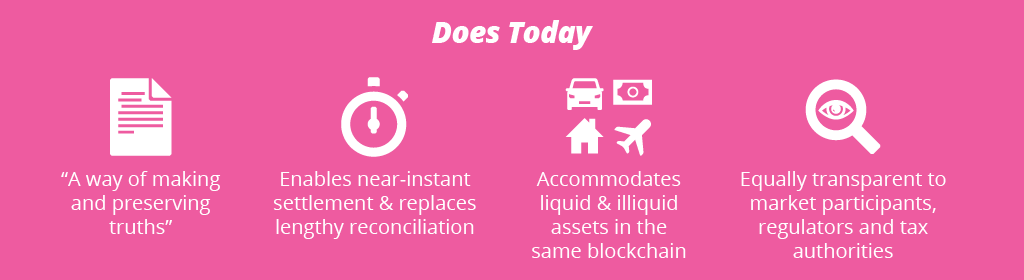

Let’s start by looking at what blockchain does well. It’s a ledger. It can be easily distributed among a lot of participants and it’s extremely difficult for any one of them to tamper with it. So, the most basic capability touted by its champions rings true—that it offers a “way of recording and preserving truths.” Because the ledger is shared, we don’t need as much back office gymnastics to settle trades and transfers, so trades are completed faster and overhead costs go down. Plus, we don’t need as many intermediaries since we just change the owner of the asset on the ledger itself.

While Bitcoin has grabbed most of the headlines, crypto-currencies are really a sideshow. The value that can be captured in a blockchain goes well beyond wannabe currencies: assets from bonds to bicycles can be recorded on the same blockchain without much in the way of customized infrastructure. The ledger makes every transaction visible to anyone with a copy of it, giving partial relief to regulatory and compliance guesswork.

What does all this mean for blockchain today? Merkle trees and peer-to-peer networks have been around for decades, so the tech is sound. It provides a means for transparent recording of assets and activities as well as the multiple parties involved in them, in a manner that’s cheaper than most conventional alternatives as well as highly immune to tampering or manipulation by any participant. Lots of multi-party transactions—especially complex regulated ones—would benefit tremendously from this today.

The reality of blockchain is that the tech is mature, and there is value to be created through it today.

However, we can’t let our enthusiasm get carried away: that value will be tempered for the foreseeable future by constraints and limitations of the technology and the companies that adopt it.

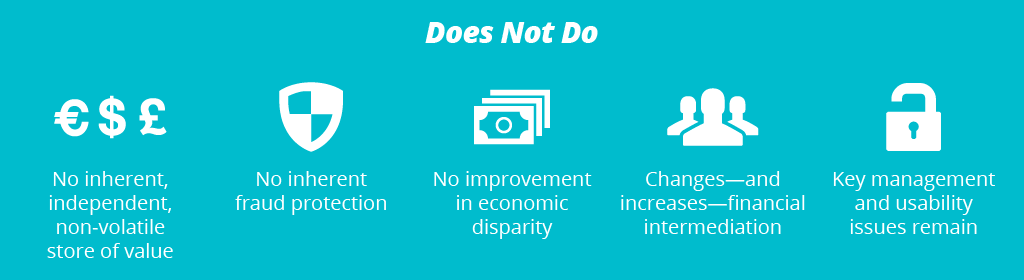

Sharing a blockchain ledger does not mean we shut down all our back office functions; it does mean we have to spend more so they can keep pace with faster settlement cycles. Exposing transactions isn’t the same as revealing counterparties, so compliance with things like know-your-customer and anti-money-laundering will continue to be a burden. And for the foreseeable future, blockchain scales in numbers of nodes, but not in transactions per second: it works just fine up to a few thousand transactions an hour, but would take a day to record less than 60 minutes of credit and debit card transactions at today’s volumes. Incumbent financial institutions aren’t at risk of obsolescence any time soon.

As we saw in the first article in the series, we’re best to check our wide-eyed utopian optimism at the door. That free side-dish of crypto-currency isn’t a genuine store of value. Maintaining security requires a private key that few know how to keep safe and still fewer can possibly remember. It doesn’t offer guaranteed immunity from fraud and it won’t make the world of commerce a fairer place by itself. Plus, as much as it simplifies, it’s not hard to imagine somebody getting the bright idea of selling bonds against fractions of bundles of fractional claims on blockchain-registered cashflows, each collateralized by blockchain-registered assets.

That mouthful of complexity tells us that intermediation isn’t going to go down in a blockchain world, it’s going to explode.

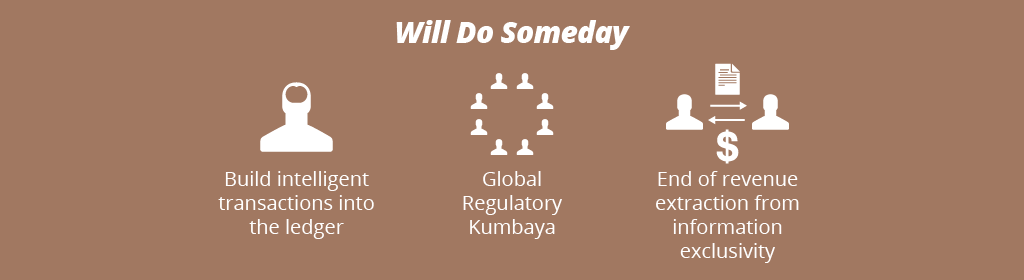

One of the most ambitious goals for blockchain are “smart contracts” that transform shared ledgers into a “world computer” while transforming businesses into a collection of networked algorithms. This isn’t that far fetched an idea, since it’s a direction all organizations have been heading since the first commercial computers arrived. But it’s still a long way off. Smart contracts function like algorithmic trading: they are at risk of overreacting to market data, being gamed by other people’s algorithms, and are susceptible to self-inflicted deployment errors that wreak economic disaster. Converting our business to autonomous code sounds great until we realize that code has to be resilient against behaviors, intentions and conditions that are (today, anyway) impossible to model or protect against.

Even a marginally complex smart contract can easily become a self-targeted weapon of mass financial destruction.

Blockchain can be an enabler of more ambitious goals. Want to know what's really in that burger, or that collateralized debt obligation? Blockchain can provide universal transparency into the provenance of complex assets, whether financial or manufactured. Need to know who you're trading with, or that they really own the thing you're trading for? Blockchain creates a means of codifying everything from identity to assets. Worried about risk building up, or complex money-laundering across financial institutions. Blockchain allows us to monitor activity in near-real-time.

But these aren’t problems that will be solved solely by technology. They’re choices made by industry incumbents, regulators, and governments about how markets function. Those choices reflect the needs and fears of the past, and the desire to protect the balance of power in the present. Nobody would choose to design a distributed trading system for financial assets using partially duplicative, inconsistent ledgers that needed to be married up, days after a trade takes place. A regulator—pick one from among the SEC, DTCC, CFTC, OCC, Finra, CFPB, the Fed, and many more—could insist that asset transfers happen in real-time and are recorded on a shared, open ledger. This is technologically achievable today, but it isn’t a technology problem: achieving it requires a change in the direction that the regulatory winds are blowing. As the stalled Honduran Land Registry shows, governments aren’t fixed with a piece of technology: these are ultimately questions of societal values and will.

What’s real about blockchain, then, is a dichotomy: the modest commercial terrariums that can be built on blockchain ledgers now are a shadow of the sweepingly different ecosystems they promise. The gap exposes the marketplace dynamics, power structures and systemic inadequacies that are concealed, or taken for granted, in current commerce. Once brought to light, they can be challenged by innovators and regulators alike: why shouldn’t we expect a system to self-regulate and absorb exceptions, rather than imposing penalties on its members for failures and mistakes? Today, we can build terrariums and ask really interesting questions; following through with complete ecosystems is still a long way off.

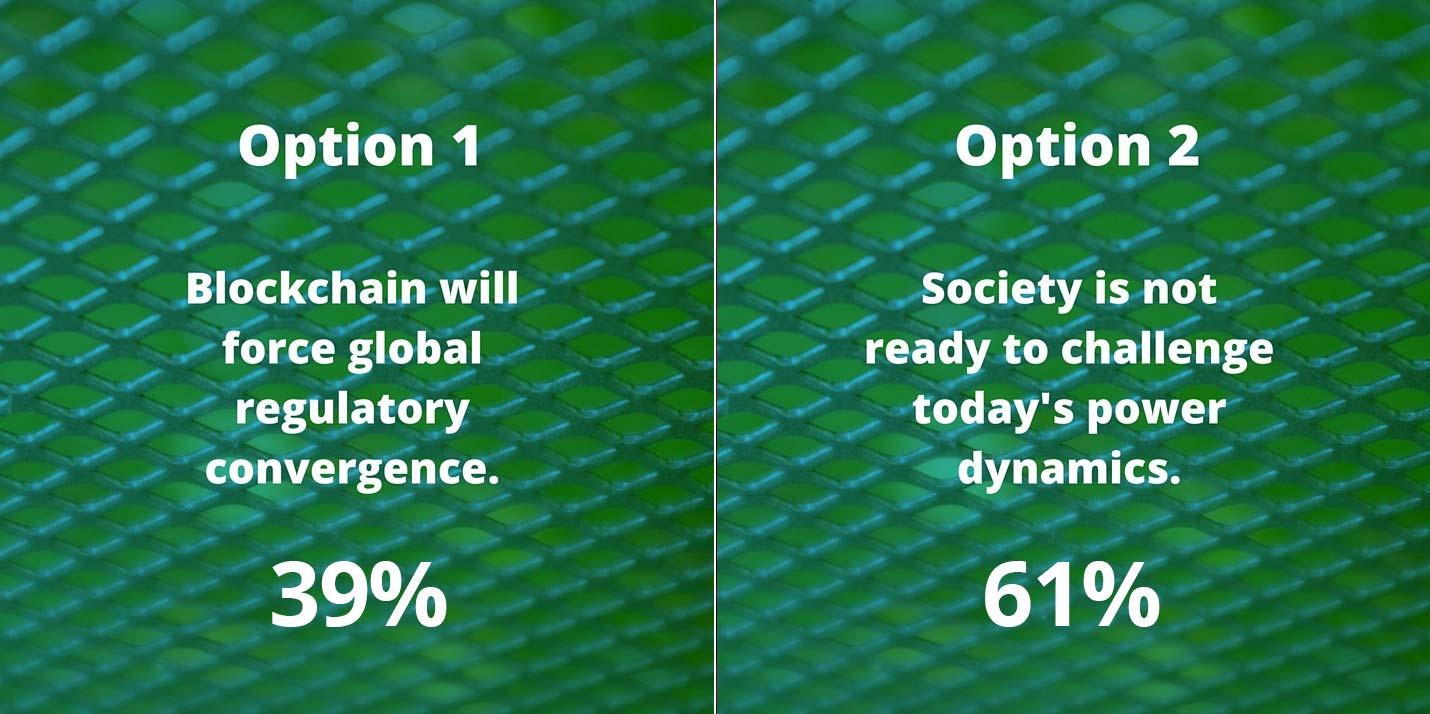

Update: Here are the results from a recent poll by readers of this article

Disclaimer: The statements and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the positions of Thoughtworks.