What Kevin Bacon Can Teach Us About Decision Making

"Six degrees of separation" is the theory that that everyone is six or fewer steps away from any other person in the world. The theory was proposed by Frigyes Karinthy in 1929 and popularized in the 1990s by the parlour game "Six Degrees of Kevin Bacon."

Here we are 86 years later and I’m proposing a different theory involving degrees of separation. From observing decision making in organisations, it appears to me that the greater the degree of separation from a particular issue, the less the likelihood of making a good decision on how to deal with it.

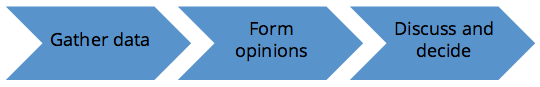

Let’s look at how an executive makes a decision that is likely to have an impact on the business of his or her organisation.

1. Gather Data

Data, including a description of the issue and its likely effects, are gathered. This is most likely to come up the chain of command and arrive at the desk of the executive. It could be in the form of an escalation by a customer, a disaster in the market place, or an innocuous report by someone who spies a problem and wants to get it resolved.

2. Form Opinions

Next, the executive will likely invite opinions on how to address the issue from who he or she deems to be “informed parties.” These, other than the executive itself, could range from research agencies and fellow execs, to project estimation offices. In some cases, it might even include the people who identified the issue in the first place.

3. Discuss and Decide

Finally, depending on how hierarchical the organisation is, there will be some sort of discussion where the various opinions will be presented, discussed and one chosen.

Interpreting Data

In most decisions, the underlying data that is needed to make the decision is often abstracted away by degrees of separation, usually via people. Rather than base a decision on facts or actual data, often executives have no choice but to depend on interpretations of the facts or data by people who work for them. In one case I witnessed, an executive was required to make a decision on the future of a business unit based on a report from a group of fact-finders who never actually visited the business unit but relied on historical financial reports to perform their analysis.

In some cases, it is a matter of convenience that they choose to listen only to trusted advisors. Regardless of the reason, the result is that quite often, decisions are taken without having all the facts on the table and by people who may not be close enough to the data to understand its implications.

When it comes to organisations that are trying to leverage technology to further their businesses, it is no different. You see budgeting decisions made for business units and product lines by people who have never met a customer in their lives, yet need to help decide whether it makes sense to allocate funding for products which are supposed to attract new customers.

Prioritisation of feature sets for products are often made by people who are not close enough to realize the ROI impact of making those decisions, and most often do not realize the inter-dependency in various product lines of their own organisation well enough to prevent their delivery teams from clogging up their pipeline of work.

So, What's the Answer?

The answer is simple – push decisions downwards. Delegate and empower.

The two need to go hand in hand since the folks who are now going to take decisions need to have the authority to implement the change needed as well as take responsibility for the execution and the outcome. The role of the Product Owner, for example, in a software product team is precisely that. The Product Owner needs to be connected to the business and the reality of the customer’s world so that they get the right data to be able to decide what to build for them, and at the same time, they are given the authority to follow through on their decisions and get things done.

Since it isn’t easy to do this in an organisational culture which might be ingrained with most decisions being made at the top, here are a few tips to start.

Ask yourself if you need to be the decision maker. When an issue comes to you, stop yourself from deciding on it and try and identify someone in your team who you can trust to take the decision.

Start empowering people. While at first your team member might hesitate to make a decision on his or her own, provide support in terms of being available to bounce their ideas off you.

Allow people to fail fast. It’s likely that some decisions you delegate will not have positive results. Rather than pull those back into your realm, allow them to continue owning decisions in those areas, but encourage them to learn from the early failures.

As an executive or manager, you need to start measuring your degrees of separation from where “the work” is happening. While there is no magic number like six, you will see that when you try to reduce the separation, especially when trying to decide on issues, you are more likely to enable better decision making by yourself and by your team. And isn't that the true measure of an executive?

Disclaimer: The statements and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the positions of Thoughtworks.