Part 1: Understanding the implications of Open Banking on the financial services industry

The financial services industry has been undergoing a significant shift globally, and now in Australia following (among other things) the recent Royal Commission into Misconduct in the Banking, Superannuation and Financial Services Industry, and the introduction of a Consumer Data Right (CDR) in late 2017.

The CDR was introduced to support consumers to compare and switch between products and services, and encourage competition between service providers. The result? More innovative products and services with better prices for customers.

The concept of consumer data sharing for better services is not a new one in Australia, typically used for automatic payments or account aggregation. The way data sharing is done today however, via screen scraping, is neither secure nor legally regulated. In today’s model, a consumer shares their credentials to the recipient organisation, effectively handing over the keys to their financial life. This is where Open Banking comes in.

Open Banking will be introduced in phases, with phase one (basic product information) taking effect from 1 July 2019. This means that financial institutions must provide consumers with access to their data, should the consumer request it, in a prescribed format via a set of secure APIs (application programming interface).

From 1 February 2020, consumer data for mortgage accounts, credit and debit cards, and deposit and transaction accounts must be made available to consumers, and between July 2019 and February 2020 the legislated aspects of the CDR will be formalised.

In the first 12 months of applicability of Open banking in Australia, only the ‘Big 4 Banks’ (ANZ, CBA, NAB and Westpac) considered Data Holders under Open Banking regulation. Any other market providers including Authorised Deposit-Taking Institutions (ADIs), fintechs, or comparators who want access to this data remain classified as Data Recipients under the regulation. From July 2020, all Data Recipients will also become Data Holders.

Under Open Banking, both the banks (the Data Holders), and the organisations who receive the data (the Data Recipients) must handle and store consumer data in a secure, regulated fashion until such time that they have the consumers’ permission to use it. Once this permission expires, the data must be de-identified.

Conceptualising Open Banking: What is it really?

Open Banking on its own is a misnomer. It’s actually a set of three concepts that together empower the financial services customer to access better services for themselves:

Concept 1: Each consumer owns the right to their data.

Concept 2: This data is stored on their behalf securely and with their permission, in a financial institution like a bank.

Concept 3: The consumer, has rights to share this data, via a secure channel that banks/financial institutions have to provide, to any other organisation of their choice, in order to get better services specially suited to them.

While we may be behind adopting the initial concept of Open Banking in Australia, we are ahead of the international financial markets as our regulation is written as a broader CDR – that is, if implemented well, it will positively impact the average consumer’s life well beyond their financial transactions.

CDR and Open Banking in Australia: How is it defined and regulated?

Three key organisations have regulatory control over the components of CDR and Open Banking in Australia. They are:

-

The Australian Competition and Consumer Commission (ACCC) (responsible for setting up the platform and policies that facilitate Open Banking regulation)

-

CSIRO Data 61 (the Consumer Data Standards body, responsible for creating API standards for transferring data, taxonomy, the customer experience standards etc.)

-

Office of the Australian Information Commissioner (OAIC) (safeguards consumer privacy and data security standards for Open Banking)

Under this regulation, Data Holders are required to build systems with the ability to securely share the data of their customers across most retail banking including current accounts, savings accounts, deposits, loans and mortgages, and business lending.

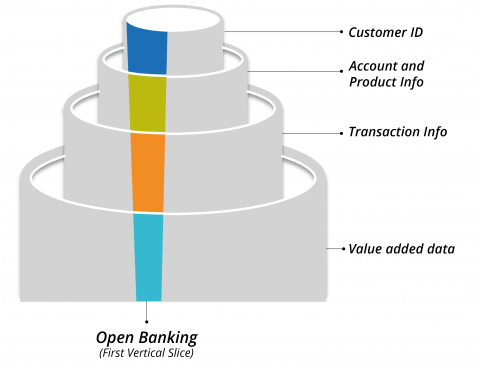

Customer Data is defined under the Treasury Laws Amendment (Consumer Data Right) Bill 2018 as:

-

Information shared by the consumer (consumer identification information)

-

Information about the consumers’ use of products (account balances, products used, interest earned, transaction history etc.)

-

Information about the products themselves (all types of deposits and mortgage products etc.)

A fourth information subset known as Value Added Data is still ambiguous under the regulation. This subset is part of a second round of consultation under Australian Government review, after which CDR is likely to proceed to become law.

The ACCC (responsible for setting up the platform and policies that facilitate Open Banking regulation) requires the following levels of compliance for accreditation:

For the Data Holder and Data Recipient

-

Demonstrate their ability to capture customer permission, authentication and authorisation

-

Share this information with the Data Holder for confirmation

-

Receive data via the Open Banking APIs

-

Demonstrate their ability to securely store this data and de-identify this data once permission or use expires.

For the Data Holder (in addition to the above)

-

Demonstrate the ability to receive the request from the recipient

-

Identify, authenticate and authorise the customer

-

Reauthorise their permission, and have APIs ready and available for the Data Recipient to transfer the requested data.

To test the practical application of a permissioned request from a consumer for data sharing, Thoughtworks partnered with Data61 to create a minimum experience standard for a Consent Flow for mortgages. This was tested with a cross-section of customers.

When are these changes taking place?

The original timelines tabled in the Treasury Laws Amendment (Consumer Data Right) Bill 2018 were as follows:-

July 2019: The ‘Big 4’ banks prove readiness to share information across all applicable areas in retail banking (mortgages excepted)

-

February 2020: The ‘Big 4’ banks prove readiness to share information including mortgages and business lending

- July 2020: Other ADIs prove a readiness to share data across all applicable data sets.

These deadlines have shifted by almost six months, and are currently looking something like:

Beyond CDR into Open Life

Beyond CDR into Open Life

Treasury Laws Amendment (Consumer Data Right) Bill 2018 is the government-led legislative change that has established Open Banking in Australia under the CDR.CDR operates under the premise that the Citizen owns the rights to their data, and they have the ability to share this data in order to obtain personalised service that best suits their needs.

Open Banking is essentially the first vertical slice of CDR. The regulation talks about future plans into other verticals as well, clearly calling out how Australia will move beyond Open Banking, into ‘Open Utilities’, ‘Open Telco’ and ‘Open Energy’ in the near future.

While Open Banking gives us a platform from which to share our financial data to get the best financial services, it is limited for now to just the betterment of our financial needs.

When we can share data beyond just banking, to a future between banking, utilities, telecommunications and even retail, then the consumer is in true control of their data across all parts of their life. This is what we call true Open Life at Thoughtworks.

The next article in this series will look at the implications of Open Banking on the consumer.

Disclaimer: The statements and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the positions of Thoughtworks.

Beyond CDR into Open Life

Beyond CDR into Open Life