Finding the "right" people: Part 2 of CD for Executives

In my previous blog, I introduced the case for why Executives need to get a handle on CD. In this blog I detail the first baby step in your organizations CD journey -- getting buy-in from the "right" people.

As organizations (and the projects they undertake) grow in size, they reach a point at which they need to split people into teams. The most common approach to such a division is to create teams around functions and appoint managers for each team - a development manager to manage the developers, an operations manager to look after the operations teams, a QA manager for the testers, etc. The newly created management layer is incentivized based on the performance of their team; therefore they have a strong tendency to align themselves with the needs and goals of their team and will look after the team's interests. The first challenge in introducing CD into such an organizations is identifying the people that need to be convinced of the value that CD will bring to them. Who should this person (or people) be?

Us vs. Them Example A

A few years ago, I was introduced to a large corporation in central Europe. We (Thoughtworks) were called in by the Head of Development to help them improve their delivery process. Very quickly it became apparent that the main issue they were faced with was with the complete disconnect between the agile Development teams and the Operations teams. The two sides were based in different locations, formed parts of different organizational units and reported to different management structures.

We engaged with the Operations people in an effort to simplify and automate the delivery process but we found it extremely difficult to get them to see things "our way". We spent a bit of time trying to understand this issue and found that the Operations unit was simply reacting to the way they were incentivized. The Operations team was judged by the level of uptime and the number of incidents reported. This made them very untrusting of anything foreign to any of their environments or processes. In this particular instance we were able to make some tactical improvements but the overall level of separation and mistrust remained.

Us vs. Them Example B

Earlier this year I was invited to spend a couple of days with an organization in Germany. The invitation was from the Head of Testing and he wanted me to work with him on selling CD practices to the other two parts of his organization (Development and Operations). Looking back, one thing that was different about this engagement was that during my visit I kept hearing the participants say things like "the CEO is pushing us to embrace CD practices" and "if you have any problems involve the CEO into the conversation". The engagement was intense and there were numerous challenges and disagreements, but in each case we were able to come together and think about what we should do that will satisfy the CEO's need for faster and higher quality deliveries. After two days I left the team with a clear vision of where they wanted to go, an agreement on what needed to be done and a set of short-term goals that they were going to work on in the next three months.

Buy-in makes the difference

There are many differences between the two examples I've mentioned above, but the main one in my mind was around the level of commitment from the senior management for the CD initiative. In many cases I see, one team or one part of the organization is looking to change things, however the rest of the organization does not see this change as their highest priority and this is where the friction starts building up. In my conversations with the Head of Testing from that German company I made this perfectly clear. His main goal was to convince his counterparts (Head of Development and Head of Operations) that all three areas need to care more about CD practices, and this was always going to be a difficult sell. Ultimately what made it possible was that the manager overseeing all three areas (CEO in this case) was already on board. Hence we were able to ensure that the goals and incentives for all three areas could be changed to align around creating faster, more frequent, high quality production releases.

So whom should you get buy-in from?

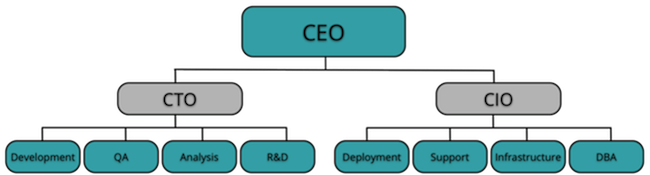

Many large IT organizations I've visited over the years have implemented an organizational structure similar to the one above (Figure above). In their case the CTO is a person responsible for driving the innovation and moving the company forward, while the CIO is responsible for day-to-day operations of the organization and "keeping the lights on". The organizational challenge for anyone trying to introduce any kind of significant change in such an organization is that they would have to sell their idea to both the CTO and CIO, or alternatively get the buy-in from the CEO. While this is definitely achievable, it is by no means an easy task, and it also introduces a significant bottleneck, as it is usually very hard to get a significant amount of time from the people in these functions.

Who are these "Executives" that we need to convince of the benefits of CD practices? This is a question with a very simple answer that requires you to perform two simple tasks:

- Identify the teams and functions that are involved in the full CD lifecycle (this is usually done as part of the Value stream mapping exercise)

- Create an organizational chart showing all these teams and functions and the management structure responsible for them

All you need to do now is follow the org chart until you find a single position that has responsibility for all the teams and functions you identified. That is your target audience!

Stay tuned for the next step (and the next blog in this series) -- Changing the team structure.

Disclaimer: The statements and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the positions of Thoughtworks.