User Research Will Destroy Your Product

Properly used, user research will destroy your product. This is a feature, not a bug.

You have an idea, maybe even a great one. You’ve done your design sprint, your visioning session, your intense few days of white-boarding. You’ve built your draft roadmap, have a few personas and a well-worn copy of the Lean Startup. No plan, though, survives its first contact with the enemy.

Lean methodologies praise the power and impact of user research without actually talking through how to use it. Product managers, particularly in the enterprise, have piles of competitive, quantitative outputs, and analytics reports. Startups have budgets to hand out gift cards to participants in coffee shops, and both think they’re doing it right.

Talking to your customer is hardly a novel idea. Keep in mind, mold is over a billion years old. Penicillin was only released in the 20th century. Just because something exists doesn’t mean it’s useful to you, especially if you’re not using it the right way.

In that vein, get ready for a bitter pill.

The Lies We Tell Ourselves

In too many process implementations, 'value' is a convenient fiction. Agile and Lean teach us to drive to value and to frame everything in the context of the user’s need. This results in backlogs full of stories that start with the dubious 'as a system' and with UI tweaks. Noble ideals have a way of leading us astray if we don’t think critically about them.

Our understanding of value in this context is anemic and cheap.

To reclaim the word, a product is a promise of shared value: lasting commercial and competitive benefit for the provider and ongoing unique fulfillment for the consumer. Like a handshake, it only achieves its purpose in the moment that the two collide.

I’ve already talked about the importance of 'unique' in that definition: Markets crowded with me-too solutions are reduced to bowls of oatmeal — homogenized, boring, and different only in incidentals.

Value, though, is how we crack open 'fulfillment' in the above definition.

Risk and Reward

Pirate metrics (Acquisition - Activation - Retention - Revenue - Referral) were popularized by Dave McClure of 500 Startups as a funnel to describe an engagement model for B2C companies. While each stage is a fundamental change in the nature of the relationship of the user to the product, I want to focus on the middle, Retention. Stickiness and the realization of value in the product lives there.

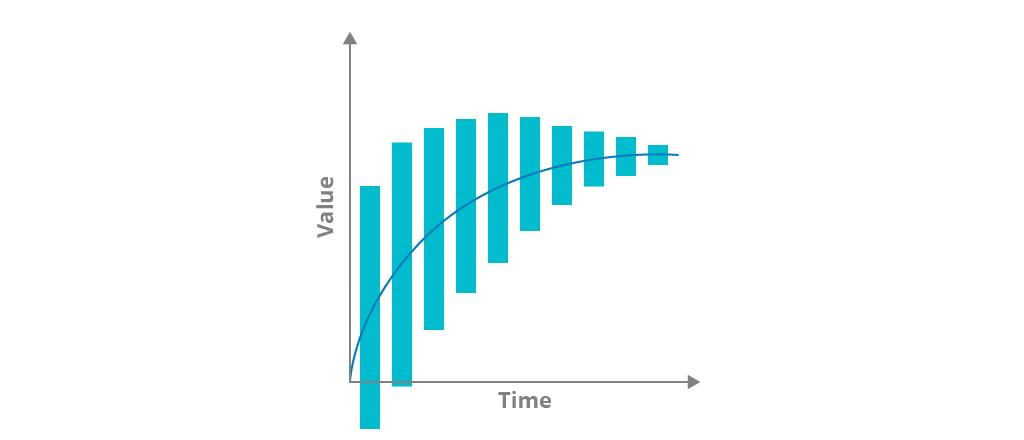

Hypothesized value is where you test, and the model for measuring the return of user research is iterations of Risk and Reward. Your risk is composed of two costs: the cost of staging the test (whether as ethnographic observation, qualitative interviews, panels, sending out a survey, setting up the clickstream analytics, etc.) and the cost of being wrong (your sunk cost in what you’re testing). Reward is pretty simple; it’s the benefit of being right.

The ratio between risk and reward is not stable over the course of taking a product from concept to customer. Like a functional test smoke suite, the first few tests are highly valuable: Do people need this? Does this product create fulfillment? Have I made what makes my company different and amazing a critical part of this product and how it works?

Over time, your focus narrows as you pass those broader, qualitative tests: Does this feature work? Can a different design or interaction paradigm improve the performance of this KPI? As you move from 'should' to 'how', your questions get smaller, and so your reward gets smaller too. Like all iterative testing frameworks, your process suffers from diminishing returns.

The relationship of risk and reward over the lifecycle of a product is therefore described logarithmically — rapid advancement and value from the early stages of the investigation to stable and shrinking return in the later stages. Because of this, both the beginning and the end of the journey encourage the most dangerous behavior.

Big Bang

The first tests are unquestionably the riskiest; the fate of your idea hangs in the balance. You use them to establish the fitness for need for the idea. These tests establish the boundaries within which the fitness for purpose for the product’s features and capabilities live and develop. Your first tests are the gladiatorial arena for your idea.

In organizations without a core testing principle, the risk borne by the first tests balloons the longer they don’t vet their ideas. This is never worse than when they commit the cardinal sin of a Big Bang release. The sin of the Big Bang is either fueled by fear of being wrong (so why wouldn’t you stop earlier?) or a case of mistaken identity: the idea has been conflated with its implementation.

There’s an inherent amount of risk in the first tests—don’t make it worse by expanding that risk beyond the potential reward value. You end up shouldering higher premiums on that risk for the same information that other organizations are getting on the cheap.

The Narrows

In a psychology paper published last year, Wagenmakers et al. said, “A single experiment cannot overturn a large body of work. […] A strong anvil need not fear the hammer[.]” A healthy research capability develops the 'strong anvil' of your product – you can develop and evolve your product with confidence, and validate your instincts against customer feedback and behavioral analysis. With an established track record of tests and successful reactions to the test results, no single test or line of inquiry is going to break the world.

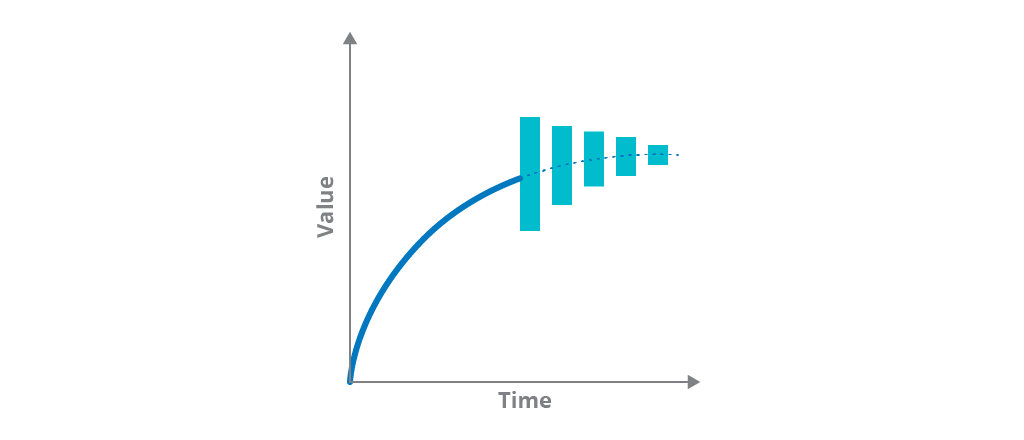

But as your line of inquiry narrows from idea to implementation, and from implementation to options within an implementation, your potential benefit faces dramatically reduced returns on the costs of the research. There are only so many 'red vs. blue buttons' and 'tabs or hamburger menu' tests that you can put into the field.

There is a minimum cost for any research initiative, whether the developer time to implement new tags for your analytics platform, the time to write a script to walk a customer through the application flow, or the cost of that Starbucks gift card to thank your customer for their time and consideration—you’re paying someone something for that information. You must ensure that the information you’re getting is worth what you’re paying for it.

The Narrows, as the risk-reward loop of research becomes neutral and smaller, are the more dangerous location on our curve – it’s unusual for digital organizations never to have heard of user testing and willfully do big-bang releases (accidentally is another matter entirely). Overusing testing and falling prey to the narrows is all too common, though.

The danger of the Narrows is simple: If you’re spending all your time and money in your research budget fine-tuning a finely tuned instrument, your competitors are already looking for the next opportunity.

The Narrows are just another kind of stagnation, and it’s a sure sign that a major pivot or breakthrough capability set is needed. When dealing with the chilling effects of a stagnated roadmap, a product manager should purposefully introduce risk as a way to unlock potential new reward. Escaping the Narrows requires a step change to leap out of it: modifying your product to break into adjacent markets or evolving from one product into a platform play to leverage network effects.

Your competitors are hungry and trying to out-innovate you.

First Contact

No matter how clever or well-conceived the roadmap, every user test I’ve been a part of has produced insightful, interesting, and actionable data. The produced product always was different from the planned product—and better too. That plan didn’t survive first contact with the user, and the user research—happily—destroyed my product.

The usefulness of any given test is measured against its subject, scope, and the outcomes of all the prior tests.

This means that the user testing framework for any product incurs diminishing returns over its lifecycle. While modeling this return as iterations of risk-reward, there are two dangerous periods in the testing harness: the earliest and the last ones.

Early tests run the risk of having uneven distribution of risk, especially considering more sophisticated solutions that have advanced too far into their implementation. Big bang releases, surprise launches, and other isolationist tactics bear significantly higher risk premiums than collaborative and iterative investigations advocated by standard Lean practices.

Later tests, with narrower scope, run the risk of stagnating the product’s advancement of value by confusing activity (staging tests and analyzing results) with progress (incremental or dramatic production of value). The narrowing risk-reward cycles mean a step-change (pivot, launch, or new market) should be introduced to drive the product to higher levels of lasting value.

Lean on research smartly—answer the big questions for your stakeholders and checkbook-holders (should we build this thing at all?). Connect with your customer in ways that ensure they benefit from all the hard work you and your teams have done (be the penicillin, not the mold). Understand when you have a stagnating product and push it out of the nest; find a new market, a new segment, or re-imagine your role in your customer’s life.

Properly used, user research will break your product. It also will show you the way to pick up the pieces.

Disclaimer: The statements and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the positions of Thoughtworks.