Why Lean Enterprise Transformation is Hard

Everyone knows that big cross-organizational change is difficult. However, not all organizational transformation is the same. This is particularly true for businesses looking to become fundamentally more entrepreneurial, the lean enterprises that create original market value as a repeatable core competency.

The transformation to becoming a lean entrepreneurial enterprise faces unique challenges for business models; it relies on silo busting and cross-organizational collaboration.

What's a Lean Entrepreneurial Enterprise?

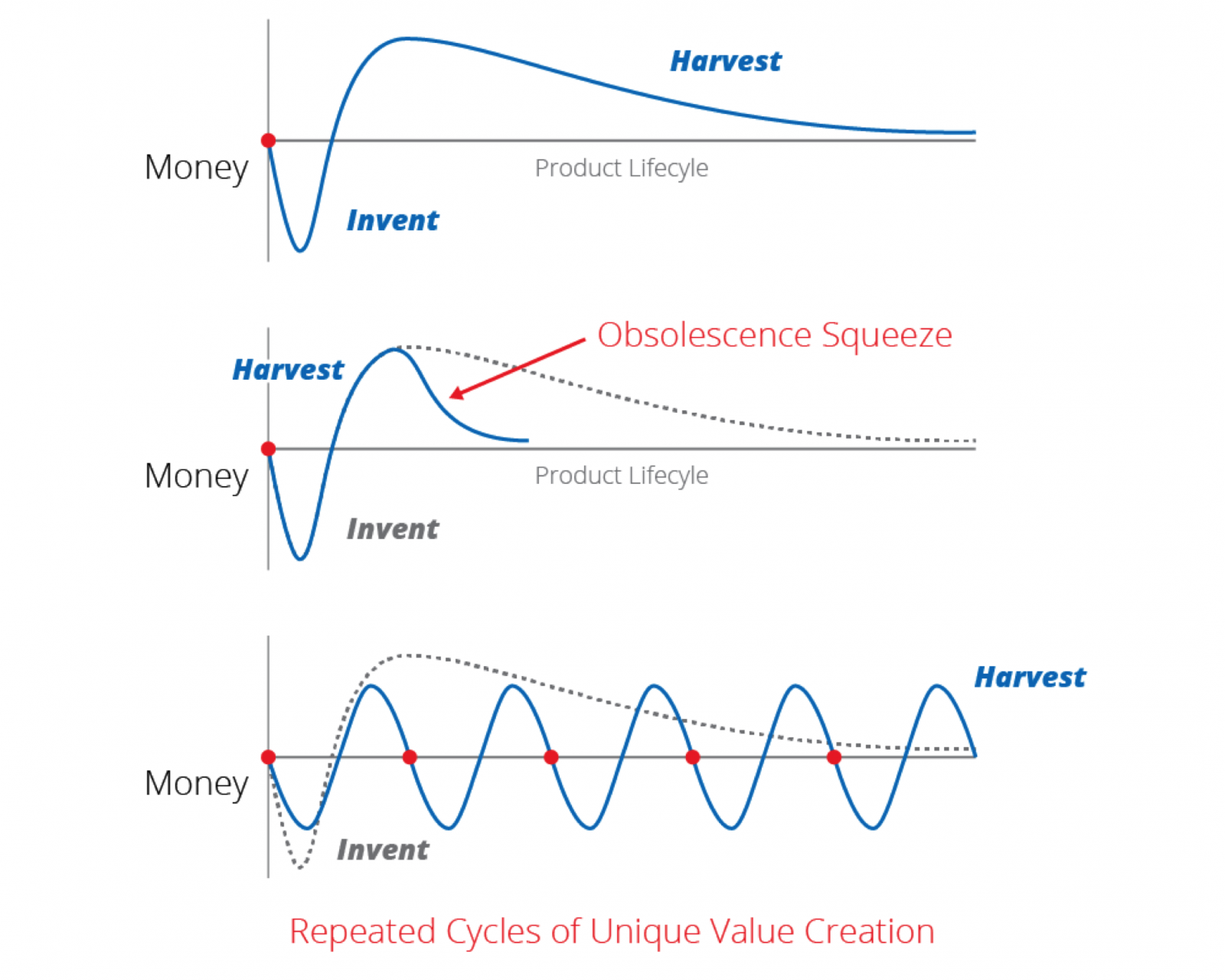

Rapid advances in technology, a growing global creative workforce, and a market with fewer and fewer barriers to entry are driving a hyper-creative marketplace. New ideas make established business positions obsolete with disturbing frequency. Products and services that do survive are exposed to commodifying price pressure.

This world demands the ability to repeatedly develop innovations that uniquely matter in the marketplace. Few traditional organizations are prepared to put this level of innovation front and center in their firms. An Entrepreneurial Enterprise recognizes the fundamental market shift that has occurred and seeks to build an organization that discovers, shapes and brings innovations to scale as part of its core business operation.

Technology plays a key role in an Entrepreneurial Enterprise, since technology is at the core of so many fast-moving, high-value products and services. However, the capabilities of an Entrepreneurial Enterprise cannot be limited to the IT department. This is a transformation that spans the entire organization, from top to bottom, across silos.

Change the Problem, Change the Strategy

At the root of every major enterprise transformation is a shift in the problem the organization is trying to solve. For organizations working in a traditional, stable, and slowly evolving market, the challenge is building assets that improve efficiency and scale performance.

Traditional business assets are built in this reasonably stable environment. Managers assure the predictable delivery of initiatives, exerting control over development by breaking big projects into fixed pieces. Processes typically have a formal linear structure that allows each step to be performed in relative independence.

In contrast, innovators working in a hyper-creative marketplace don’t have the luxury of a stable business environment or proven business solutions. Their challenge is discovering and building new ideas while the market rushes forward around them. For them, capitalizing on new opportunities is the driving business need.

Traditional plans and control structures are inappropriate for this environment. Pretending that opportunities can be defined up front, clearly evaluated and remain stable all while a step-by-step business process runs its course ignores the reality of changing markets. There are too many unanswered questions, complex interactions, and shifting needs.

Instead, the enterprise must become radically more responsive. This creates a leadership paradox. Flexibility and creativity are needed, but simply trying to duplicate the startup culture of Silicon Valley inside the organization’s walls is impractical.

There is a need to balance investments, coordinate efforts across the business, and do complex things at scale.

Command and control models establish specifications at the beginning of a step. The work is then done and the output compared to the original specification. Philip Crosby, one of the pioneers of quality management practices, claimed that “the definition of quality is the conformance to requirements”. This is a powerful driver for reducing defects by doing it right the first time, but it is built upon an assumption that the starting point was correct and worthwhile in the first place.

In a market defined by complex innovations and change, entrepreneurial enterprises recognize the impossibility of delivering on this core assumption. Instead, they reorient their thinking of what good looks like to be more in line with Gerald Weinberg’s statement that “quality is value to some person.” The market demands more than doing it right. It requires creating original value that matters.

This drives the need for an alternative model of guidance and coordination. In an Entrepreneurial Enterprise this comes from the use of feedback loops. Learning Loops exert control in a fundamentally different way. Someone makes their best guess at a design or architectural choice, work advances far enough to produce new insights, and finally the path forward is adjusted. These Build-Test-Learn loops focus on business outcomes, not simply the completion of a piece or work.

This is similar to what we do when driving a car. We start with a broad plan of where we want to go, but constantly gather new information along the way: braking, steering, and adjusting course in response to road conditions, traffic, and discovered opportunities (“we can cut through the Walmart parking lot and avoid that traffic jam up ahead”). It seems that this test-and-learn model is a natural metaphor for leading an organization in an ever-changing marketplace, yet traditional enterprise leadership is far closer to a command-and-control version of the car trip.

The Enterprise as a Big Learning Loop

Agile software development teams have been using these feedback loops for a number of years within the scope of individual projects and teams. They have proven to be powerful tools that deliver working software with far greater consistency than traditional waterfall models.

This is a testament to the power of feedback-driven learning, but it is not an enterprise operating model.

It isn’t enough for the organization to have isolated pockets of market-driven learning and response. The surrounding business processes for budgeting, design, deployment and training are just a few of the groups that impact the real-life agility of an agile technology team. Carving out creative ghettos like Innovation Labs is not much better. Such isolated small-scale efforts typically have limited impact on the broad fortunes of an organization.

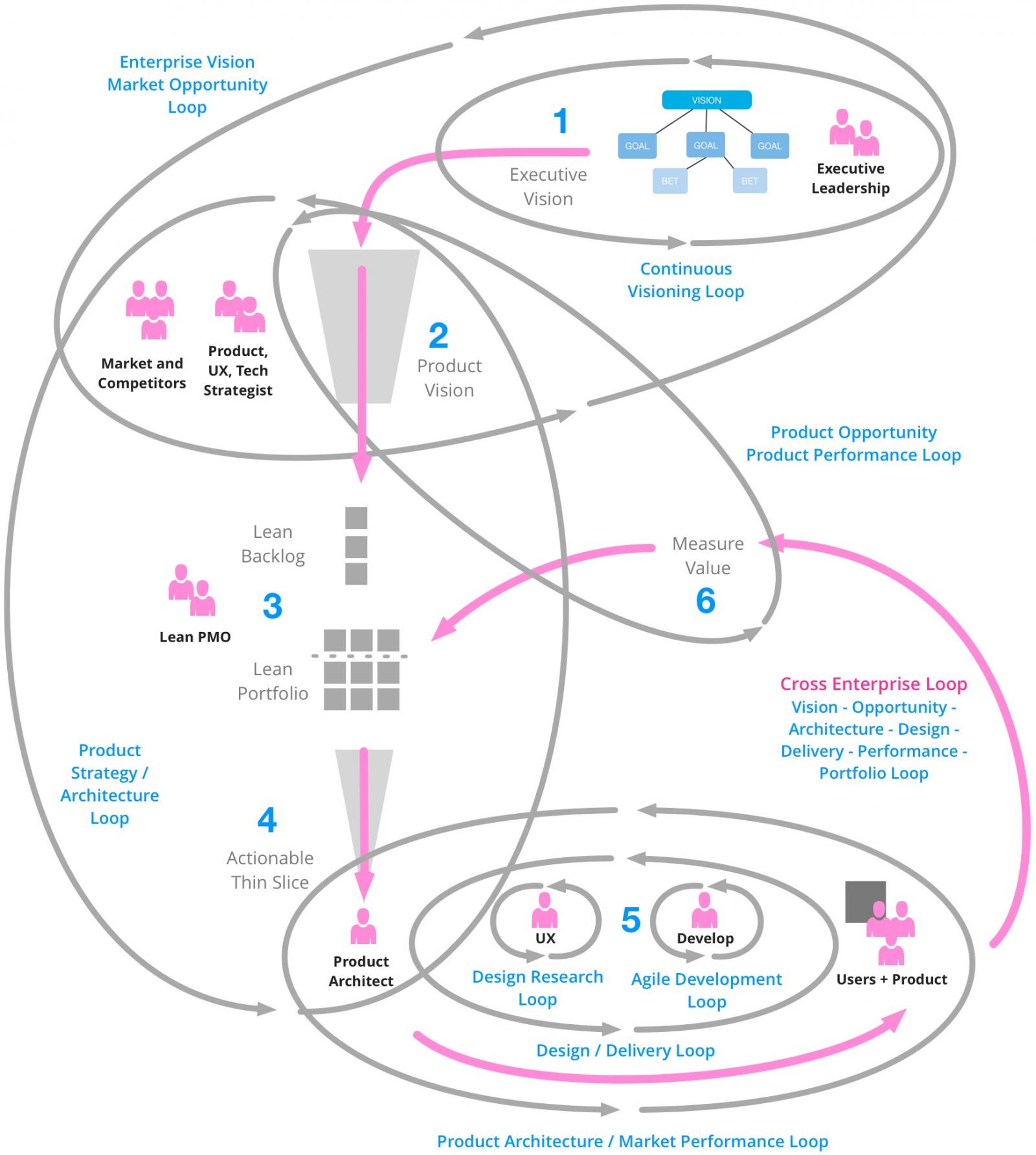

To be creative at an enterprise level, the entire organization must be involved in the nimble pursuit of new opportunities. An Entrepreneurial Enterprise does this by leveraging learning loops throughout the business. At a macro level this manifests as a large loop designed to identify opportunities, build and test them, and then respond strategically to new performance insights.

Loops within Loops

Transforming an organization to this structure is difficult for several reasons. Mindsets must shift from one based on taking or giving orders to one expecting a continuous stream of new insights. It represents a deep change in perspective and approach.

If this was the only challenge, it would still be enough to partition the business into parts and work through each functional silo one by one. In a lean enterprise model, multiple learning loops are needed to coordinate and control different aspects of the innovation process. Product ideas must align with organizational strategy. Designs must be integrated with technical delivery. Product performance must be balanced against product opportunity to define the portfolio of work.

Our neat diagram above is not so neat in practice. At least ten different learning loops contribute to selecting, shaping and delivering the product and then evaluating its performance. Some of these loops are limited to a single team, while others span diverse parts of the organization.

A traditional business process has convenient seams along which processes can be divided. For example, the workings of a traditional budget committee can be updated without involving the Java developer down the hall. That’s much less true for the collaborative loops that span a learning-driven Entrepreneurial Enterprise. Instead, three types of dependencies must be accounted for:

- Local Team Dependencies (easy): A team can alter their processes without directly impacting others in the organization. For example, an individual development team can independently choose to shift the way it manages its work in progress tasks.

- Cross-Team Functional Dependencies (difficult): Multiple parts of the system must change in lock step. For example, the Enterprise Vision loop requires participation from Executive Leadership, Product Strategy and Strategic UX teams. The Product Opportunity / Portfolio Loop requires the participation of both the PMO and Product Strategy teams. Even though these loops cross role and functional boundaries, all parts need to be in place in order for them to function.

- Enterprise Culture Dependencies (epic): There is a need for a comprehensive shift in core values or goals that drive the processes. For example, the organization’s cultural thinking must shift on what the important measures of success are, moving from getting work done to creating competitive advantage.

Negotiating these dependencies is the messy challenge at the core of transforming a traditional organization into an Entrepreneurial Enterprise.

Many executives, well-schooled in a business structure with clear seams and divisions, naturally compartmentalize their thinking when envisioning change. They may ask how the proposed shift affects their budgeting or how the change impacts delivery teams. Unfortunately, this neat decomposition of the problem doesn’t work in a highly interconnected business ecosystem.

Cross enterprise dependencies are easy to overlook when advancing new technology practices.

For example, Delivery Teams are often excited by the possibility of responding to market feedback by releasing code to production more often. Facebook and Netflix make this sound like a bold choice. This is a great idea, but still far from a strategy that can be implemented by the delivery team in isolation.

Consider all the hidden dependencies. If a delivery team can release at will, who coordinates training users on the new features? How are changes aligned with the planned evolution of the brand vision? When do controls like validating legal compliance occur?

Some interactions can be surprisingly esoteric. For example, how are financial capitalization rules managed for a product that has no fixed deployment date?

Tools of Change

An interconnected enterprise with real-time learning is a powerful tool in the marketplace, but the complexity of interconnected collaborations can easily overwhelm organizational capacity for change.

Fortunately, there are three techniques can help wrestle with this complexity.

Embrace the Big Scary Picture

The whole picture needs to be visible and understood at the beginning of the journey. Don’t start by subdividing the problem along traditional organizational seams.

First, it avoids oversimplifying the transformation strategy. It often seems convenient to organize the change process in ways that align with existing organizational structures. This can easily cut across the collaborative loops that are the foundation of a successful learning-based system.

Second, a big-picture view exposes the scale and level of involvement in the change. No one gets to sit on the sideline. There will be many, many changes and there must be a genuine readiness for the scale of this journey.

Lay a Foundation with Islands of Change

While the big picture exposes the overall journey of transformation, some initial changes can be made by selectively dealing with those the Local Team Dependencies described earlier. These are relatively isolated.

For example, a development team might adopt agile delivery techniques without changing the rest of the world. A shift in the approach to executive visioning might also be expanded as an early foundational step.

Islands of Change produce quick wins in areas of lower risk while promoting readiness for bigger, more systemic changes. Keep in mind that these are low hanging fruit of the transformation effort. The hard parts still must deal with system-level change.

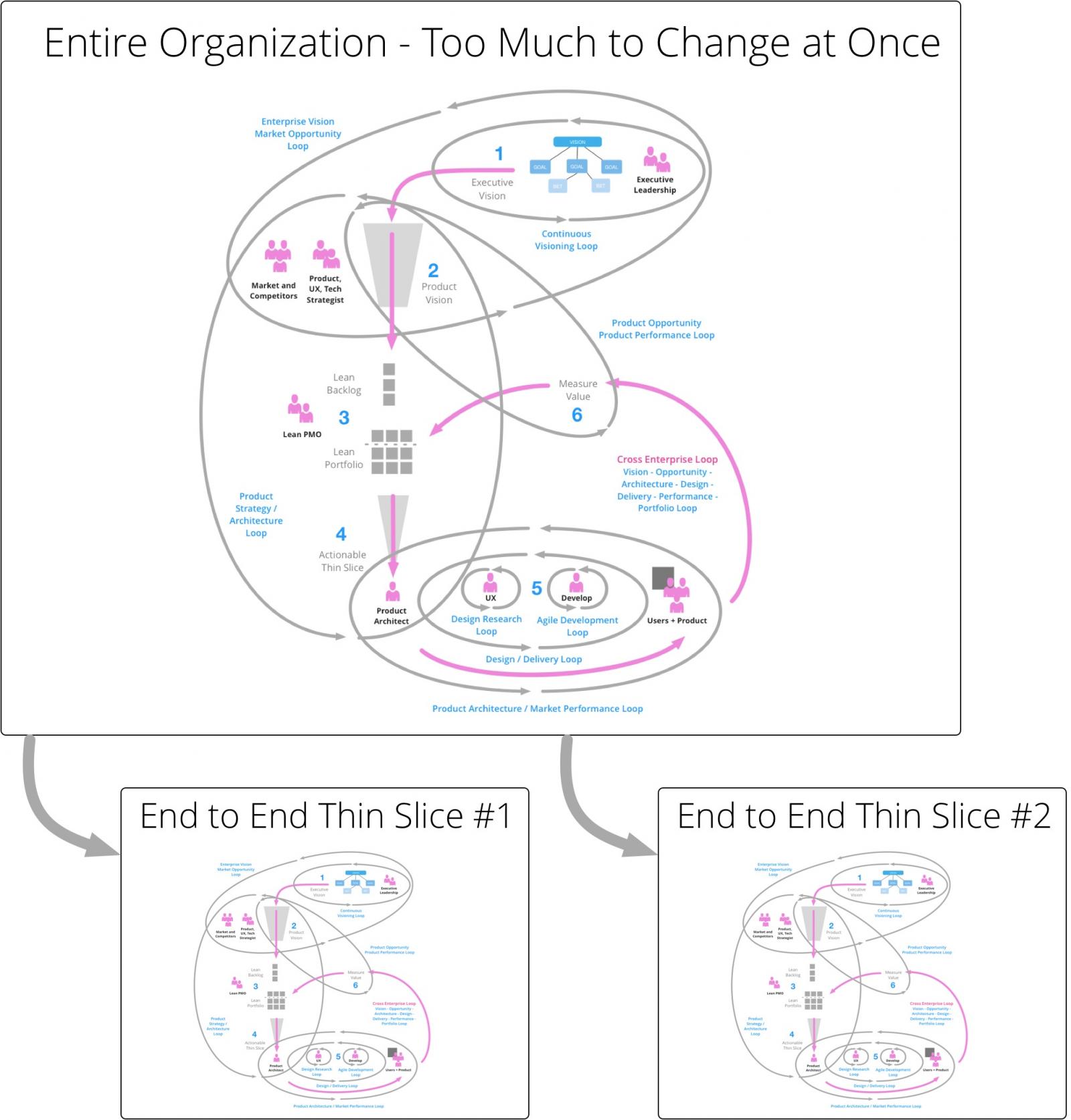

Thin Slices Across the Dependencies

System- and enterprise-level dependencies put the transformation effort between a rock and a hard place. On one hand, broad change cannot be done by cutting across the feedback loops. On the other, making big cross-enterprise changes involving multiple groups, deeply disrupting their thinking and work, is nearly impossible at scale.

The solution? Take “thin slices” that keep all the parts of a feedback loop intact from beginning to end, but do this for a narrow range of products or investments. In this model, an enterprise transformation might focus on one specific business opportunity, redefining its executive vision, moving it through a product exploration and architecture process, developing and deploying it and ultimately measuring it so that it can feed back into executive decision making.

Many different groups and functions must still be involved. Raise all the boats at once, so that each group is able to collaborate with the next in the loop. However, the change is made manageable by limiting it to a certain number of individuals and teams for each stage of the process. When one thin slice works, another can be moved to the new approach.

Scaling Out the Change

Leaders often view initial success as permission to put the transition on autopilot and roll it out like a training program for a new time and expense system. Rushing to business as usual is often rooted in organizational fatigue and the sense that after so much hard work, continuing the deployment ought to be getting easier.

Unfortunately, this misses new difficulties that come with moving to wide scale adoption. Starting with a big vision, claiming quick wins, and proving out thin slices, demonstrates success and build out core capabilities. However, this early stage work comes with certain advantages. Enthusiastic advocates often comprise a disproportionate share of early adopters. The skeptics, the ill-equipped, and the outright opponents of the change increasingly dominate later adoption. Further, programs that fit well with the fast-moving, feedback-driven models of the Entrepreneurial Enterprise tend to be selected as the first areas of change. Yet, as change progresses there will inevitably be more teams that fail to fit neatly into the new model.

Finally, broad-scale adoption forces increasingly hard choices. Some who have made long-term contributions under the old paradigm simply won’t have a place. Less-than-elegant exceptions will be needed for some activities driven by different business concerns, and other activities may be discontinued altogether.

Final Encouraging Words

The transformation into Entrepreneurial Enterprise is genuinely difficult, but it can be done. Embrace a big picture view, build up islands of skill, and leveraging thin slices all help deal with the underlying complexity of the change. It is possible to demonstrate progress, recognizing that there will be a need to continue the effort with the same build-test-learn approach that drove early success.

Today’s hyper-creative marketplace is insistent and uncompromising. Organizations must have an institutional capability for repeated original innovation and the ability to adapt to rapidly changing opportunities. This is a challenge with no easy answers, but it is a journey well worth the effort.

Disclaimer: The statements and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the positions of Thoughtworks.