IoT: First the Hype, Then the Plumbing

There is much hype around the Internet of Things (the linking of machines and sensors to the Internet), but is it deserved? At its core, IoT is just the Internet, with things on it. But these things are different from the computers we are used to dealing with. In short, the IoT is the same but different.

Old news?

In 1982, Carnegie Mellon University students Mike Kazar, David Nichols, John Zsarnay and Ivor Durham wired up a soda vending machine so that they could use the finger command-line utility to see the availability and “coldness” of the soda cans in each dispensing column remotely via the Internet (then known as ARPANET). This was quite possibly the first “thing on the Internet.” Since then, millions of devices have been happily created and connected to digital networks without fanfare or hype.

So why is the “Internet of Things” gaining attention now, given that it’s not a major technological breakthrough? The IoT’s relevance today comes from the convergence of several trends:

1. Moore’s Law

Perhaps the most important trend is the continued march of "Moore's Law" (that the number of transistors in an integrated circuit doubles every two years) along with other hardware and manufacturing innovations that result in devices that are getting cheaper, use less energy and are more powerful.

2. Operating Systems

Cheaper, faster hardware is not the only enabler. Cheaper commodity software in the form of open source industrial-strength operating systems (OSs) such as Linux or RTOS (an open source realtime OS) make it trivial to add networking (via Wi-Fi or other radio protocol), and the needed software communication stack to a device.

3. Internet

And of course, there’s the Internet itself. Thanks to global adoption of open standards for how devices communicate on the Internet using agreed-on protocols—physical, link, network, transport and higher—a device can be assured once connected, and other agents on the network can communicate with it.

Easy peasy?

Well that’s it, then. Add Linux, Wi-Fi and/or an Ethernet port, and I have my connected device! Well, yes and no.

Standard architectures won’t cut it

Device-to-device communications

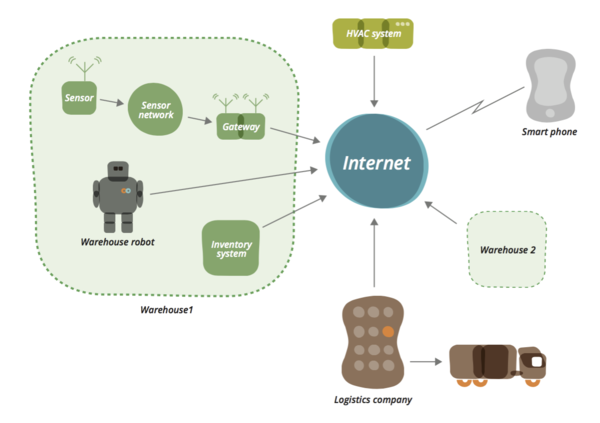

Most of the higher-level protocols that we all love and agree to use—such as HTTP—were conceived for, and are optimized for, the needs of machine, human or unconstrained server-to-server communication. Although there’s an element of human-to-machine communication in IoT and connected devices, much of the value of a connected device comes from the machine or sensor communicating directly with services and other devices. For example, let’s take a hypothetical warehouse system, as shown below. A network of temperature and humidity sensors sends information directly to a heating, ventilation and air conditioning (HVAC) system to optimize temperature and air flow in a warehouse. As stock is moved around, warehouse robots can consolidate items that need chilling into smaller areas, and the HVAC system is instructed accordingly. No humans needed.

Different design goals

The huge variety in size, battery life, deployment, form factor and functionality add wrinkles to an IoT system architecture. Take, for example, a system that has several simple temperature sensors. Each sensor needs to run on a small coin cell for perhaps five years. Being permanently on a Wi-Fi network and being able to respond to an ad-hoc HTTP GET request would drain the battery in minutes. What if it “went to sleep,” woke up every few minutes and POSTed an HTTP request to a list of interested devices? Even the most efficient ultra-low Wi-Fi device takes a minimum of 60ms to reconnect to a Wi-Fi access point. In the world of constrained devices, time is money, or at least battery drain. Given that an HTTP request is actually made up of many lower-level packets negotiating a TCP/IP session and then sending the data, this dictates that Wi-Fi and HTTP POST are not going to cut it. So much for our beloved RESTful interfaces.

New(er) protocols and standards

The solution is to start looking at lower-level protocols that work at the packet level, because these are smaller and require less power to send over the network. Several organizations and consortiums are working on defining standards for not only how to get data from a data producer to a data consumer, but also how to discover and provision devices and, perhaps more important, interoperate. In the world of human/machine interactions on the Internet, any web browser can go to any web server that supports HTTP and returns HTML. We need the same for devices. A device from one manufacturer needs to be able to send temperature events to, for example, an air-conditioning system from another.

Interoperability, it’s a large bowl of alphabet soup.

Although a great deal of work is under way in the interoperability space, it’s a large bowl of alphabet soup, with different emphases driven by industry and/or architectural goals. In the consumer electronic space, the Allseen Alliance (driven by companies such as Qualcomm, LG, Microsoft and Sony) and the Open Interconnect Consortium (driven by Intel, Cisco and Samsung) are both gaining traction, along with Wemo from Belkin (based on Universal Plug and Play). There’s also Google Thread and Apple Homekit. And the Eclipse Foundation is doing good work building open source implementations and frameworks for IoT open standards. The list of organisations jumping on the bandwagon continues to grow.

Mesh Networks

Making this all a lot more complex is that many connected devices don't use Ethernet or Wi-Fi as their underlying physical layer, and for good reason. Take the temperature sensor above. Wi-Fi is a poor choice because it’s not designed in terms of topology or specifications to be a low-power physical transport. Wi-Fi is generally deployed as a star-and-hub style network where a number of stations all connect to a single access point on specific radio bands. The range required for a device to reach the access point means that both the hub and the radio of the device must be relatively high-powered. And it isn't just power that makes Wi-Fi a poor choice. Radio is unpredictable because it’s affected by interference, reflection and refraction. So a Wi-Fi connection that has worked perfectly for months can suddenly become unreliable because someone next door started using an old microwave (true story). If your phone has a bad connection, moving it six inches can suddenly improve it. A fixed connected device might not have that luxury.

While things are still in such a state of flux, the best approach to hype is not to get suckered in by it.

Often the solution is to deploy “mesh” networks whereby connected devices all communicate with their neighbours and messages hop from one node to another. This allows for redundancy in case one node fails or is temporarily out of reach. This topography often greatly reduces the individual device power requirements. Typically one or more “gateway” devices connects the mesh to the Internet. Work in this area is continuing; well-known implementations and standards include Zigbee and Zwave. There is great work being done in Bluetooth mesh protocols and 6LowPan. Google is also driving a set of protocols, called Thread, targeted at the connected home and built on top of 6LowPan and other existing standards.

Messaging

Most connected devices will need to communicate with a service in the cloud, or allow a smartphone to control it remotely for the full value to be realized. Sometimes this is through a local gateway, sometimes directly from the device. Many systems have found that HTTP is a poor mechanism and that an event “push” model is often more appropriate. Alternatives that are beginning to be used include MQTT (a lightweight pub/sub protocol), as well as several implementations on top of XMPP (an XML-based protocol). CoAP (a UDP-based protocol) is beginning to attract attention. CoAP combines some features of a RESTful interface with low overhead and the Observer Pattern. However, for those of us interested in the (re)decentralization of the Internet, perhaps the most interesting messaging mechanism that is beginning to show up is the use of TeleHash, which provides a decentralized, secure and private messaging infrastructure.

Troubleshooting

Finally, how to troubleshoot IoT architectures is an often-overlooked aspect. We take for granted the many tools used to debug and troubleshoot the applications and devices that connect as PCs, smartphones, tablets and servers. The range of tools and the number of different manufacturers involved in an IoT implementation bring their own set of complications that must be factored into the implementation choices.

Putting it all together

So is all the hype deserved? It doesn't really matter. While things are still in such a state of flux, the best approach to hype is not to get suckered in by it.

Instead, as I have outlined, in a number of ways the Internet of Things is the same but different. The key to operating in the IoT space is understanding the implications of these similarities and differences for your architecture, your solution and your business.

What does this all mean to anyone implementing an IoT solution?

The choices and alternatives are not clear-cut. The focus should be on clearly understanding the goals and requirements of your connected architecture. However, many of your technical choices will be driven by the manufacturer of the connected devices you choose. When looking at more than a single point solution, one of the key considerations needs to be how easy the system architecture is to troubleshoot, and how security, privacy and third-party dependencies are managed. We are in an exciting age. Connected devices are getting smarter and more autonomous, and the required standards for interoperability and robust implementations are coming.

An earlier version of this article was originally published in P2 Magazine.

Disclaimer: The statements and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the positions of Thoughtworks.