Escaping the Tame Corners of Innovation

Innovation is losing its luster. I see it in meetings and conversations every day. After years of being the darling of leadership gurus, the craft of creating original value is facing a growing skepticism that borders on antagonism.

Why? This is more than an academic question. If this is simply fatigue, the inevitable byproduct of excessive exposure, then we innovators can doggedly push ahead, burnishing our portfolio of established techniques. But there may well be something more to this discontent. Innovation could be falling out of favor because it doesn’t solve important problems that really matter in our new economy.

If that’s the case … and I think it is … then we need to undertake a new set of far more difficult innovation challenges.

Five Hard Things Innovation Doesn’t Do Well

The grumpiness isn’t limited to those sitting on the sidelines of innovation. Peter Thiel, co-founder of PayPal, venture capitalist, and author of Zero to One, pointedly states that “the smartphones that distract us from our surroundings also distract us from the fact that our surroundings are strangely old: only computers and communications have improved since midcentury."

He paints a picture of the last 40 years as a period of broad stagnation overlaid by the deceptive illusion of change from a few selected technologies. This is not because we are entirely without creative skills. In fact, we have gotten quite good at inventing value in the tame corners of opportunity. We know how to optimize performance on the factory floor and can quickly develop a new web app. These are valuable skills. However, such proven techniques evolved in markets far less threatening than those on our horizon.

Today, dangerous gaps are visible in our creative toolkit. In markets increasingly driven by non-stop creative change we’re failing to do the hard parts of innovation that most powerfully drive future success.

We don’t do messiness well. To see the common themes in this failure, let’s take a closer look at the persistent black eyes on our creative record. Here are five strategic challenges that continue to thwart us.

1. Solutions: Scaling Up for Real Life

Good ideas are no good unless they can be consistently used in real life situations. It is not enough to just invent. The hundreds of thousands of mobile applications developed over the last eight years prove just how easy creating has become. Leveraging the mantras of failing fast and early user feedback we have become masters of pilot programs and standalone products.

We are far less skilled at delivering meaningful systems that deal with the tangled complexity of the real world. Last summer, Ian Gray and I wrote about about the challenges the Humanitarian Sector faces when scaling up their growing array of stalled pilot programs. Cute and easy to implement, these small standalone initiatives have proliferated to the point where resemble a warren of baby bunnies.

Despite the institutional enthusiasm for pilots, we heard a drumbeat of frustration from donors and practitioners who see a widespread inability to scale and sustain promising ideas. Pilots consistently fall short when trying to add in the robust sophistication needed for sustainable real world solutions.

For example, a new toilet design might be successfully tested with the goal of improving urban sanitation in overcrowded cities. The initial results are exciting, but the technology will have little long term impact unless it comes with answers to a long list of complicated problems, such as:

- Who will advocate for new practices in the community?

- How will cultural norms be negotiated?

- Who will maintain the facilities?

- What business model will sustain everyone’s involvement?

Another example might be discerned in the statistics for business startup success. In many ways a startup is a pilot for a new idea and success is a successful scaling of the proposition in the real world. Here the news is grim. At the well respected incubator Y Combinator, the success rate (as measured by making or being sold for $40 million), is just 7%. That’s about the same as drawing an inside straight in poker.

2. Assets: Innovating in Brownfields

We seem surprisingly willing to embrace a similarly dismal story line for established businesses. Clayton Christenson makes an intuitively persuasive case that the artifacts of past success, such as values, practices, and technology, are an anchor on future innovation. In a future driven by innovation, this is terrible news. What good is past success if it’s just a legacy weight on future opportunity?

Brownfields are admittedly messy places to create. The executive saddled with hulking legacy business systems has “simple” choices to either start from scratch, throwing out the legacy assets, or cling to old ways and abandon new markets. Neither is attractive. A far more complex option requires untangling legacy assets, creatively reusing, repurposing and replacing resources in a messy ecosystem where new and old evolve together.

Overcoming Christenson’s hypothesis should be the great creative challenge facing the marketplace’s current winners. Existing assets do make it hard to maneuver. If past success, however, is to be anything more than a future death sentence, there must be ways to leverage existing capabilities to expand an organization's opportunities. Innovators need to successfully wrestle with these opposing forces, and not simply throw up their hands, telling the CEO to spin off startups like lifeboats escaping a doomed ship.

3. Organization: Building Responsive Enterprises

In the emerging hyper-creative economy, which demands repeated original innovation the entire enterprise must respond to shifting opportunity. Most organizations are already able to stand up isolated innovation teams without disrupting the basic operations of their business. R&D centers, innovation labs, and tiger teams give the illusion that the organization is “being innovative.”

Yet, how long does it take for a leader to reorient the organization’s focus in the pursuit of a new opportunity? What are the chances that the original ideas and motivation come from within the ranks? And, perhaps most importantly, what portion of the enterprise is actually engaged in doing something new and future facing?

In an age of accelerating obsolescence and rampant commodification, islands of innovation are insufficient for survival. An innovation lab does not create a market responsible enterprise if the primary focus of the firm remains centered on harvesting established opportunities.

For many leaders this is not news. There is an explosion of interest in creating broadly innovation-centric organizations. However, this ambition requires deep, cross enterprise transformations in both thinking, structure and process.

Program teams must be fundamentally repositioned to act with new levels of autonomy. Neatly prioritized project lists vanish, so the classic skills of management must be replaced by the more complex talents of leadership. Feedback loops need to be created and honored and the pace of work radically accelerated. It remains a big messy change that few have mastered.

4. Resources: Dynamically Created Collaborations

People are the primary resource feeding creative invention. In stable markets, where competitors move incrementally against a company’s long term market positions, businesses can pick their team and stand by them. Employees are hired and durable vendor relationships established. Innovation happens inside the walls, amongst a familiar group of players.

In a far more competitive economy, where market opportunities are increasingly varied and short lived, there is a need for more and varied talent. Organizations that rely strictly on their own internal creative capacity are at a deep disadvantage. The same portfolio of skills can’t be used again and again.

In the arts, where repeated originality is a well understood market demand, shifting creative collaborations routinely draw on broad pools of talent in dynamically built teams. The Hollywood studio model, where stars, directors, and other members of the movie crew worked directly for a single studio, vanished over half a century ago. Today, large multi-skilled teams coalesce around complex creative projects with each movie drawing on a unique collection of talent. The emergence of independent film further diversified the pool of potential contributors.

Built for the moment collaborations are still uncommon in other business domains. In fields that value stability and operational predictability, much work needs to be done to opportunistically discover talent, spontaneously build networks of trust, and coordinate a newly constructed team’s efforts toward an imaginative goal.

5. Tool Kit: Delivering Cheap Brilliance

Finally, economically viable innovations must increasingly be cheap and fast. It’s no longer enough to be brilliant. On a global stage full of competitors rushing in to claim every small position of advantage, the economic lifespan of opportunities shrinks. Organizations need to be brilliant on a budget.

Yet, organizations build toolsets that optimize established business operations or the pursuit of a single opportunity. Imagine an innovator pursuing a new fleeting market opportunity. In a traditional organization they may have the same package systems as the firm down the street, crippling chances of sustainable differentiation. In response they may choose to build something from scratch, an ordeal of obtaining budget approvals, scheduling work, and testing, that may well stretch beyond the life of the opportunity.

In a fast moving market, the distance from idea to action, must be reduced. Flexible platforms centered on the ability to invent rather than optimize, could help deliver on this goal. Think of a box of Legos that enable creative teams to assemble new ideas out of component building blocks.

This demands a much different perspective on technology investment and design. Technologists face a messy uncertain future world. Creating to enable the creative acts of others is a task that lacks the concrete anchors of current business practice and requires a broad perspective of the range of possibilities in current and future markets.

The Common Thread – Messy Complexity

On the surface these challenges seem radically different from each other, but they are all united by an important theme. They are each difficult because of an underlying messy complexity.

- Coupled Choices / Conflicting Needs – Design choices for solving each challenge are linked together in a complex web of dependence. Tangled problems like this are dangerous to subdivide or simplify. Each choice creates unpredictable feedback that changes other parts of the work and in the web of cross connections, diverse stakeholders perpetually fight over tradeoffs.

- Big Problems / Diverse Domains – These challenges are large in absolute terms with lots of moving parts. To make matters worse, each problem space spans a diverse range of disciplines. Innovators must find a ways of being quite good at a wide variety of things.

- Uncertain and Unknowable – Knowledge is intrinsically incomplete. This isn’t the kind of simple uncertainty that can be quickly researched and then set aside. The challenges are filled with hidden unknowns that short of taking action are impossible to penetrate.

- Changing – There is no stable end state. All around, actors are change the playing field and new insights continually shift nature of the challenge.

Innovating In the Tame Corners of Opportunity

This inventory of complexity maps closely to the concepts underlying “Wicked Problems” as described by C.W. Churchman and Melvin Webber and the “Social Messes” popularized by Russell Ackoff and Robert Horn.

Why has the existing practice of innovation had such a limited impact on these areas? The answer lies with the challenges that are the opposite of Wicked Problems. Tame Problems have key elements of their complexity removed and so become tractable. These are the challenges innovation is good at solving.

The prior article from this series, “What is Innovation?”, explored several well-established innovation models developed in response to business challenges over the last 70 years. Let’s take a look at two of them and see why they fall into the tame corners of opportunity.

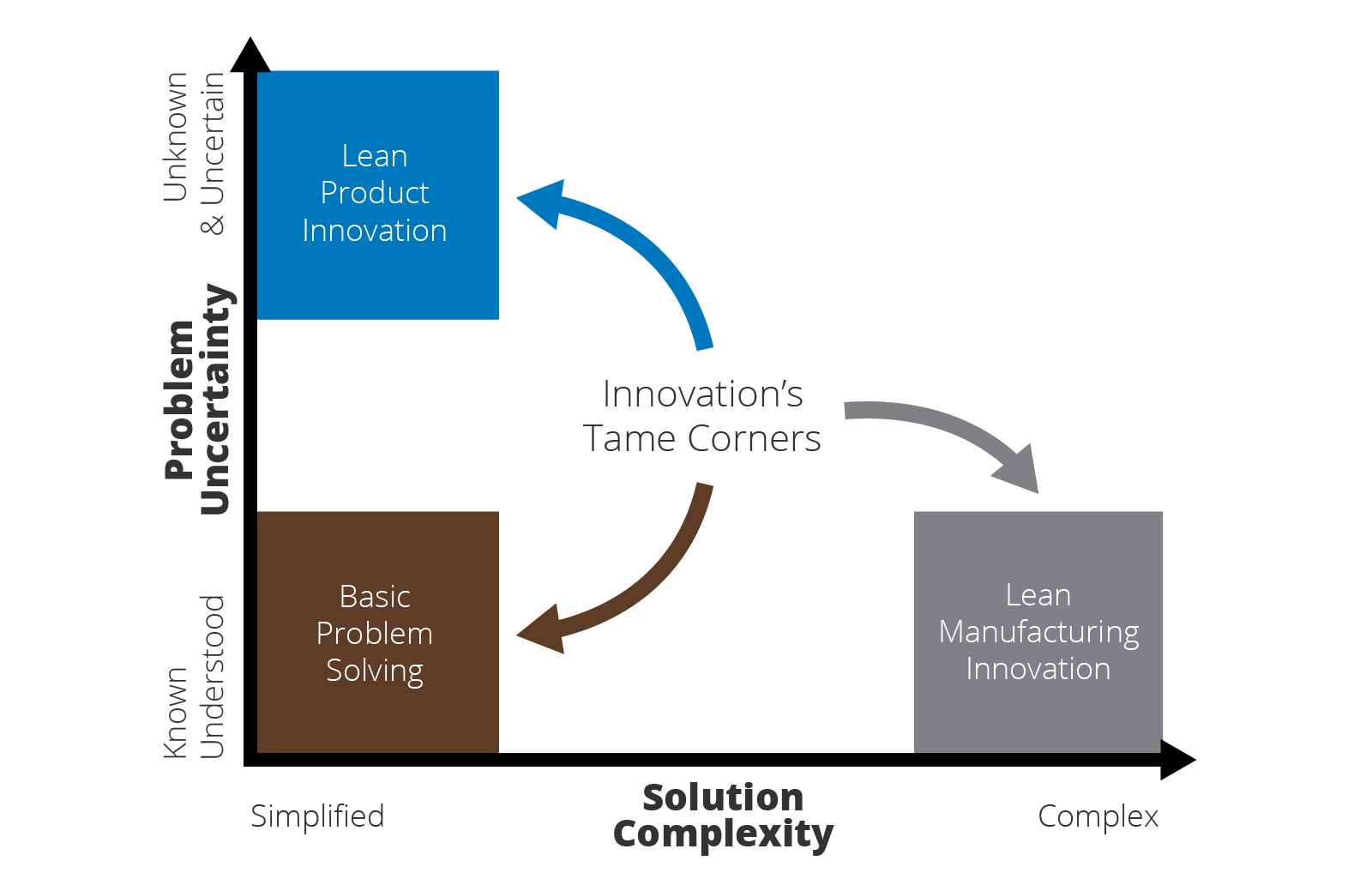

Begin by mapping them on an opportunity space organized along two axes.: one axis shows the degree of problem uncertainty and the other indicates the solution’s complexity. Work done in the lower left corner takes well understood problems with limited complexity and applies simple problem solving. This is hardly innovation at all. These are very tame challenges, the daily problems to be resolved before dinner.

If we push to the right, adding complexity but keeping uncertainty low, we enter the space where Lean Manufacturing plays. The complexity is substantial (an entire factory operation), but very well understood and documented. The problem remains tame because we have encapsulated much of the complexity in process and measurement controls.

Returning to the left, it’s possible to move up the vertical axis, wading into deep uncertainty, but diligently keeping the problem simple. This is well aligned with the user driven design and fail fast practices of Lean Product innovation. Highly speculative ideas can be explored in a tame environment as long as the overall scale and complexity are kept low.

Innovating in Complexity’s Messy Middle

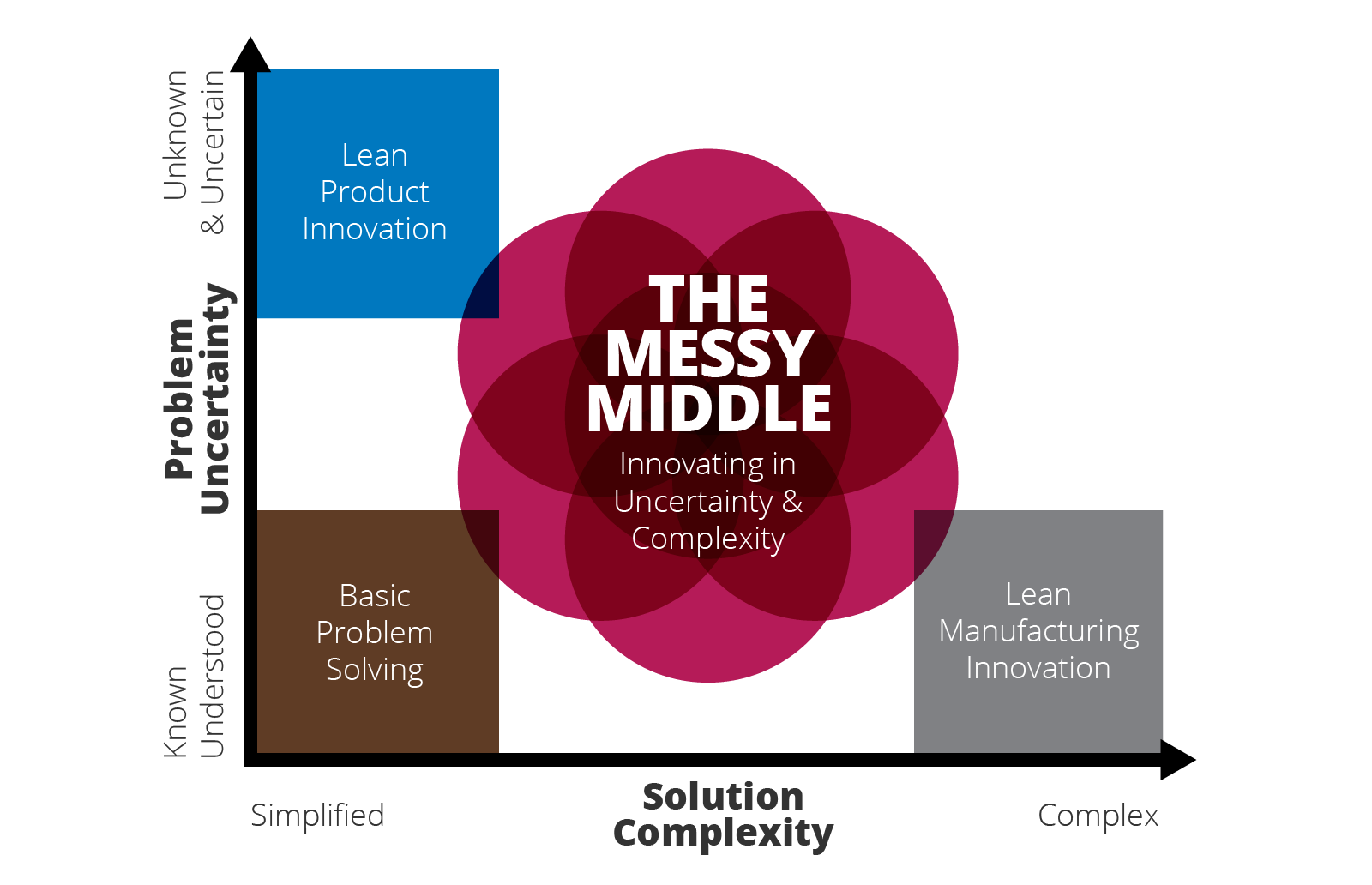

Where do our unmet complex challenges lie? They have both complexity and uncertainty and so sit in the unserved messy middle of the solution space.

It’s not surprising that existing innovation techniques fail here. The tools that rose to popularity over the last 50 years were specifically tailored to the tame corners of the opportunity space.

The inherently messy problems of scaling ideas in the real world, innovating in brown fields, creating a resilient enterprise, dynamically collaborating, and building tools for invention, can’t be simplified and shifted to the tame corners. For problems where complexity is intrinsic to their value, a new set of innovation practices is needed to embrace the messiness.

That’s the subject of the next article in the series.

This is the third article in our new series where Dan McClure shares his experiences on what is driving our new innovation-fueled economy. Read the first and second articles in the series.

Disclaimer: The statements and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the positions of Thoughtworks.