In today's global workplace, acknowledging and navigating cultural differences is more important than ever. Even the most open-minded and respectful of us can be prone to misunderstandings, perhaps because of cultural influences or power imbalances. That's why we've developed this workshop that can enable your teams to learn more about key cultural dimensions that can impact their behavior.

As a team Digital Transformation & Operations in Germany — we wanted to understand how our different backgrounds and tendencies might influence how we work together, and took inspiration from the book “The Culture Map” by Erin Meyer. Those subsequent conversations encouraged us to create a workshop format where each participant gets to hold space and share their positioning in regards to the dimensions shared in the book. After having successfully tested this approach, we want to share it broadly.

The workshop format aims to provide vocabulary and empower team members to learn, acknowledge and respect key differences.

If you’re interested in trying something similar, we’ve created a workshop template and instructions in Mural and Miro. We wish you a fruitful conversation with your team!

Walk the talk, from theory to practice

At Thoughtworks, our company culture is of paramount importance. Diversity, equity and inclusion are part of our DNA; and, for us, this means that culture is a set of lived values and principles that make working here special, enjoyable and productive. We strive to make Thoughtworks reflective and inclusive of the society we live in, regardless of age, ethnic origin, sexual orientation, gender, religion, disability, background or identity. And because inclusion and belonging is everyone's job, we are willing to lead by example.

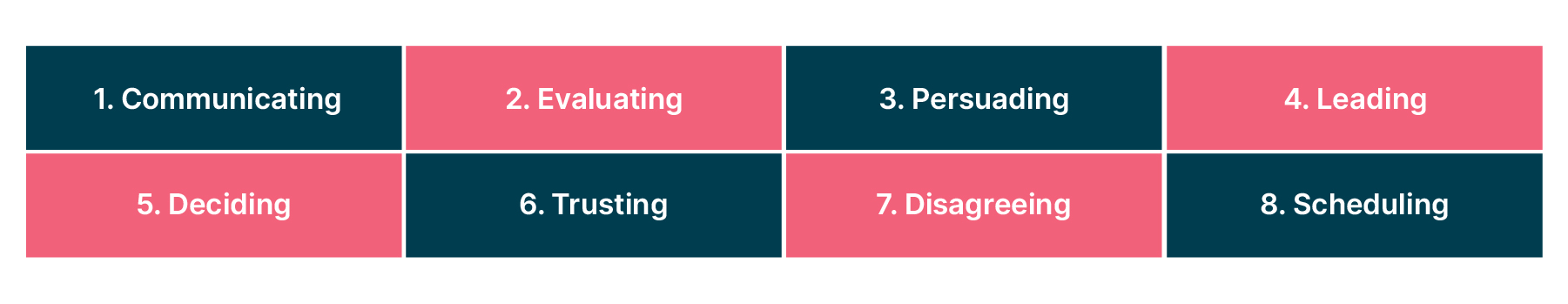

The dimensions of the culture map book

The book “The Culture Map” by Erin Meyer published in May 2014, describes eight critical dimensions of cultural variation that, if we are mindful of, can radically improve our intercultural cross-team communication:

Source: “The Culture Map”, Public Affairs, 2014

There’s obviously a lot more to organizational culture than where an organization is headquartered — it’s important to recognize the influence of someone's "home" culture: this can often override the organizational culture they are currently surrounded by. Strengthening one’s cultural awareness and those of colleagues, can help navigate common and more unusual situations in a business and in a private context as well. If you want to create a sense of intercultural collaboration, it helps if people are familiar with the vocabulary and sensitivity of the topic.

Let's look at the eight different dimensions presented in Meyer’s publication, illustrating the insights offered by the workshop we ran with our team.

Communicating

What do we actually mean when we say that someone is a good communicator? The responses differ wildly from society to society. The book compares cultures along the Communicating scale and categorizes them as high- or low-context cultures.

In low-context cultures, good communication is precise, simple, explicit and clear. Messages are understood at face value. Repetition is appreciated, as is putting messages in writing.

In high-context cultures, communication is nuanced and layered. Messages are often implied but not plainly stated. There's space for interpretation, and understanding may depend on reading between the lines.

While according to the framework, Germans tend towards precise, fact-based and clear (low-context) communication, our team member’s positions varied on the scale (see image below). Probably because, although we all live in Germany, we come from many different places.

Image shows a linear scale for dimension #1 (communication) and icons representing DT&O team member’s positions across the scale. The scale goes from left (low-context) to right (high context) with Germany positioned center-left.

--> After discovering our position, the whole team’s awareness that “communicating well” can mean something different to each individual team member increased. People on the right side of the scale can remind themselves to provide concrete examples and share more context to a situation than they would naturally be inclined to. Other team members can be motivated to ask for details and clarification.

Evaluating

Source: “The Culture Map”, Public Affairs, 2014

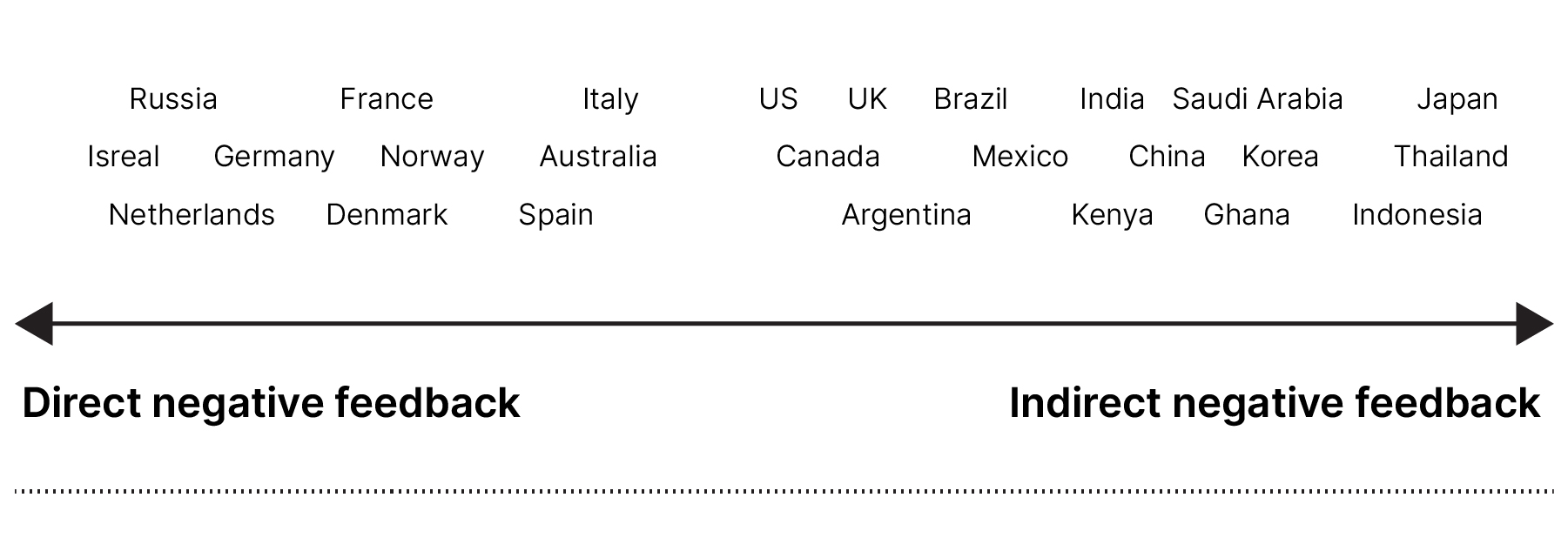

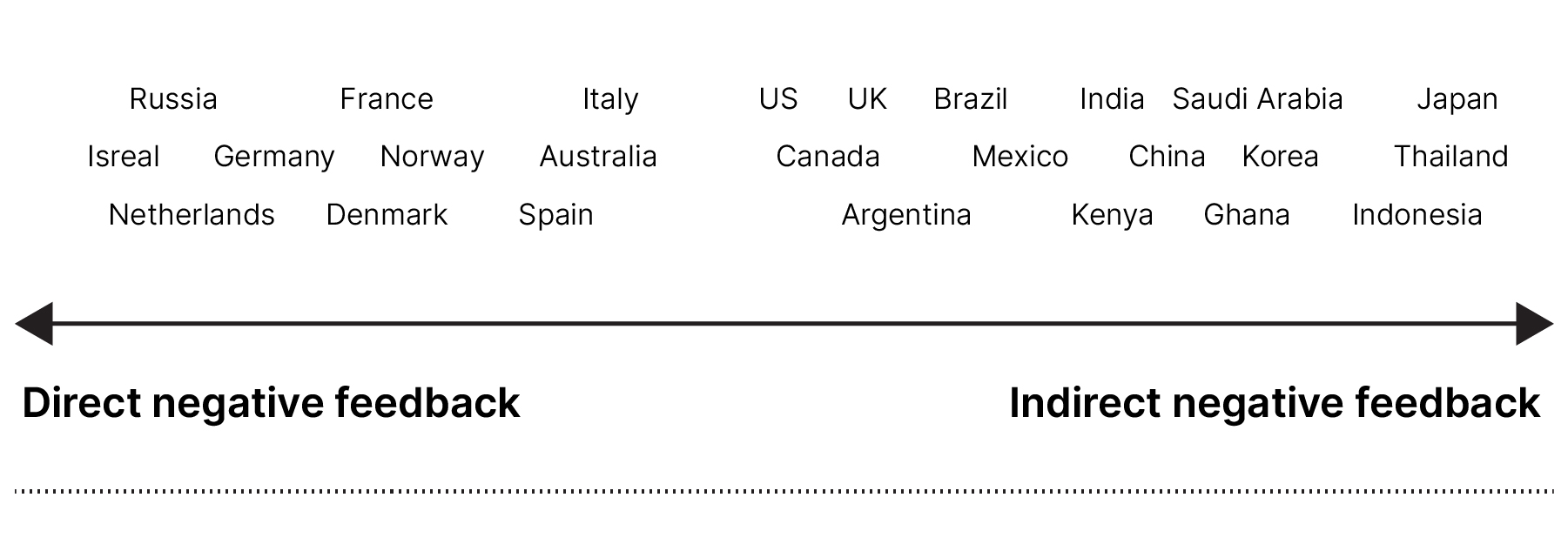

What is constructive feedback? All cultures believe that criticism should be given constructively, but the definition of it varies greatly. This scale measures a preference between frank versus diplomatic negative feedback.

In cultures appreciating direct negative feedback, such feedback to a colleague is provided honestly and bluntly. Negative messages stand alone, not softened by positive ones. Absolute descriptors are often used (e.g.: totally inappropriate, completely unprofessional) and criticism may be given to an individual in front of a group.

In cultures appreciating indirect negative feedback, feedback to a colleague is provided subtly and diplomatically. Positive messages are used to wrap negative ones. Qualifying descriptors are often used (e.g.: sort of inappropriate, slightly unprofessional) when criticizing (see for example the sandwich way of giving feedback). Criticism is given only in private.

--> In our team, most of us landed much further on the right side of the scale than the default position of Germany expects, which suggests that for keeping up team morale we should lean towards an indirect style of providing negative feedback.

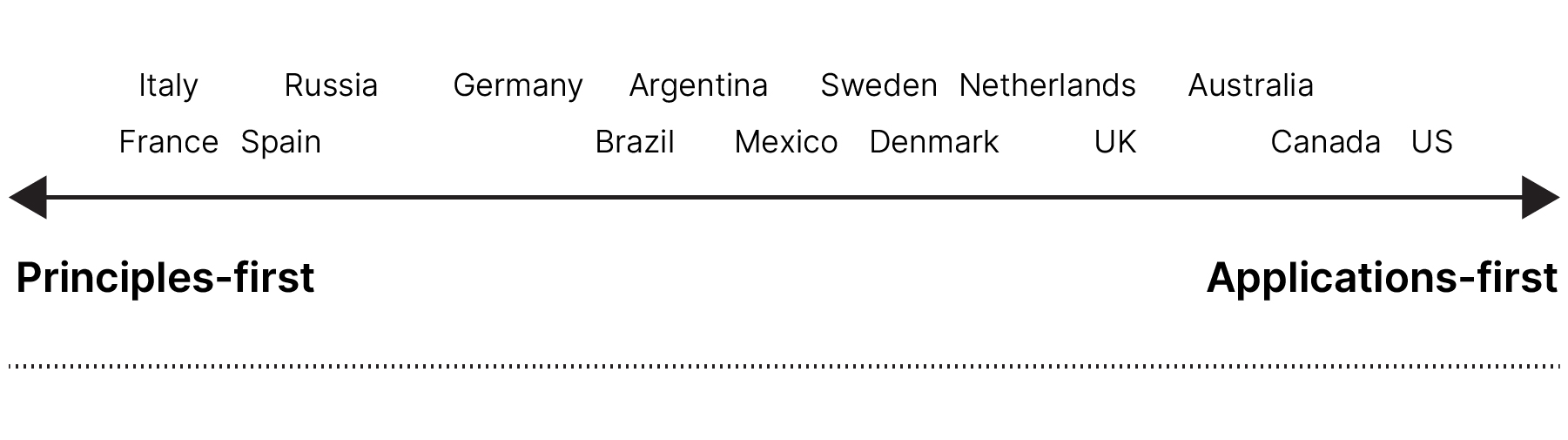

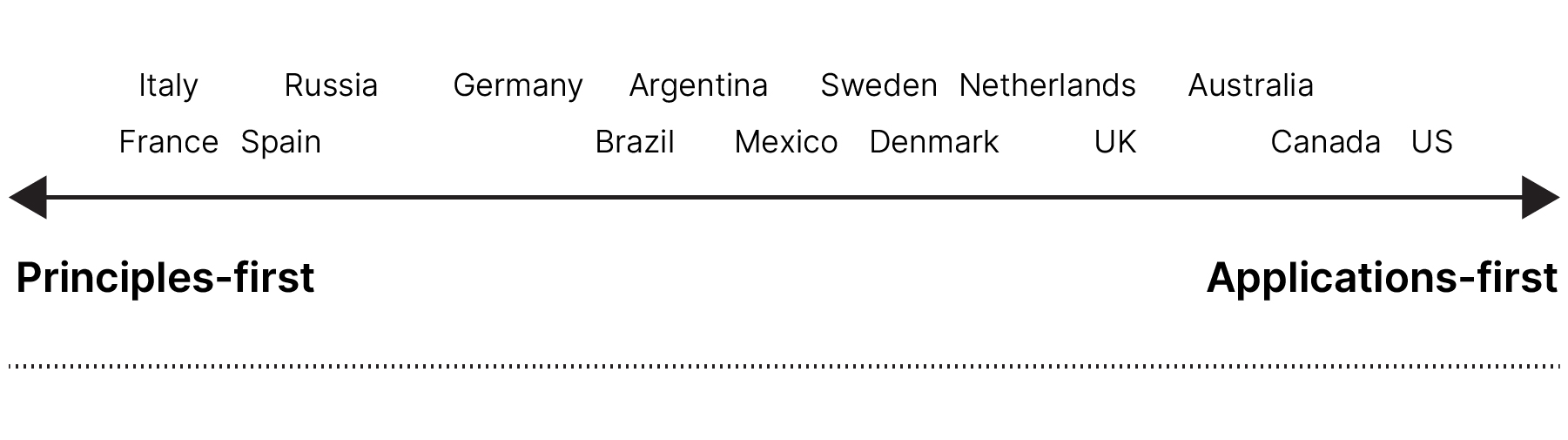

Persuading

Source: “The Culture Map”, Public Affairs, 2014

How do you persuade someone of a different perspective? The ways in which you persuade others and the kinds of arguments you find convincing are deeply rooted in your culture’s philosophical, religious, and educational assumptions and attitudes.

In a principles-first culture, individuals have been trained to first develop the theory of complex concepts before presenting a fact, statement, or opinion. The preference is to begin a message or report by building up a theoretical argument before moving on to a conclusion.

In an application-first culture, individuals are trained to begin with a fact, statement, or opinion and later add concepts to back up or explain the conclusion as necessary. The preference is to begin a message or report with an executive summary or bullet points (just like this one). Theoretical or philosophical discussions are many times avoided in a business environment.

--> While reflecting on the persuading scale, the team came to realize that also our clients vary in their degree of interest in theory versus practical examples, which we agreed was an important case-by-case consideration.

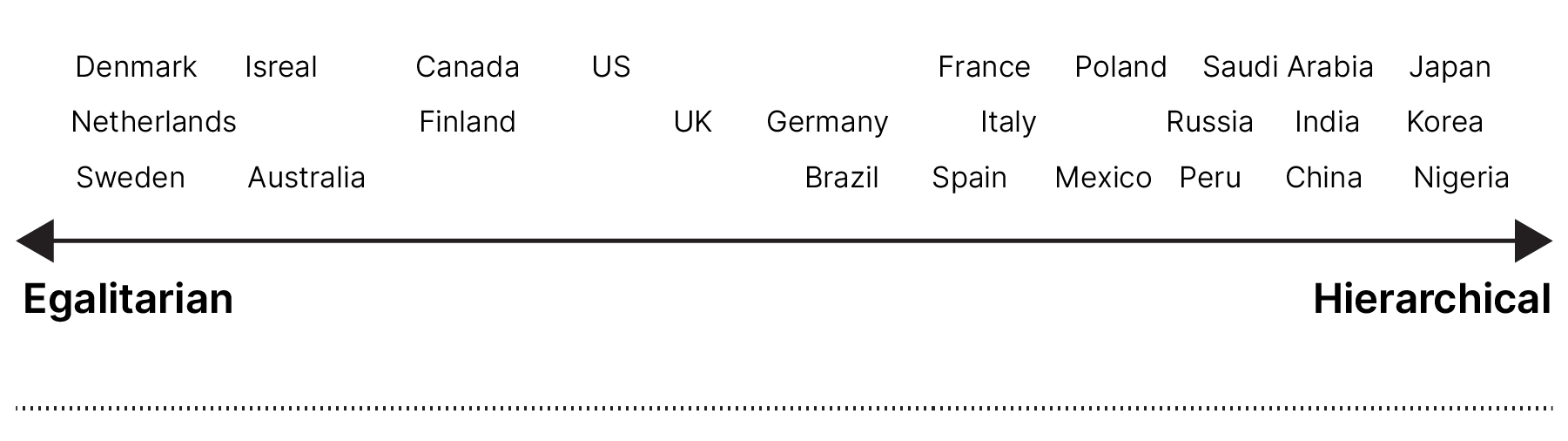

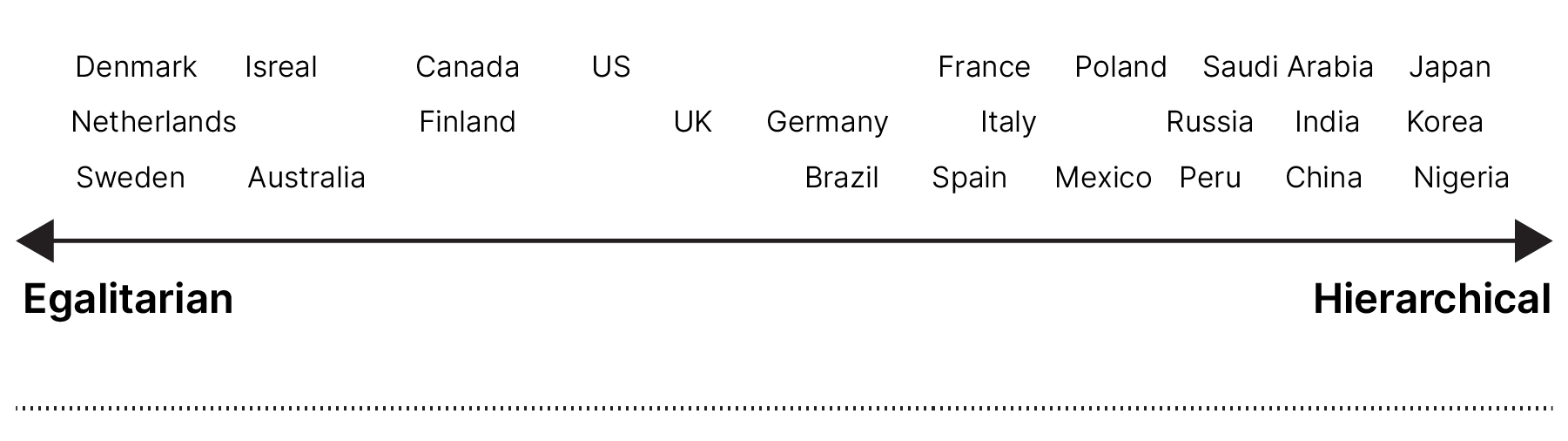

Leading

Source: “The Culture Map”, Public Affairs, 2014

What are different ways of leading an organization? This scale measures the degree of respect and legitimacy shown to authority, placing countries on a spectrum from egalitarian to hierarchical.

In an egalitarian culture, the expected distance between a boss and a subordinate is low. The ideal boss is a facilitator among equals. Organizational structures have fewer layers and communication can skip hierarchical lines.

In a hierarchical culture, the ideal boss is a strong director who leads from the top down. Organizational structures are multilayered and communication follows set hierarchical lines making status relevant.

--> In our experience, team members have different expectations with regards to organizational hierarchical levels. At Thoughtworks, we’re a network-based organization with relatively few levels of reports, nevertheless speaking to one's boss’s boss doesn’t come naturally to everyone. Some team members need to be supported more to navigate our organizational structure with confidence.

Deciding

Source: “The Culture Map”, Public Affairs, 2014

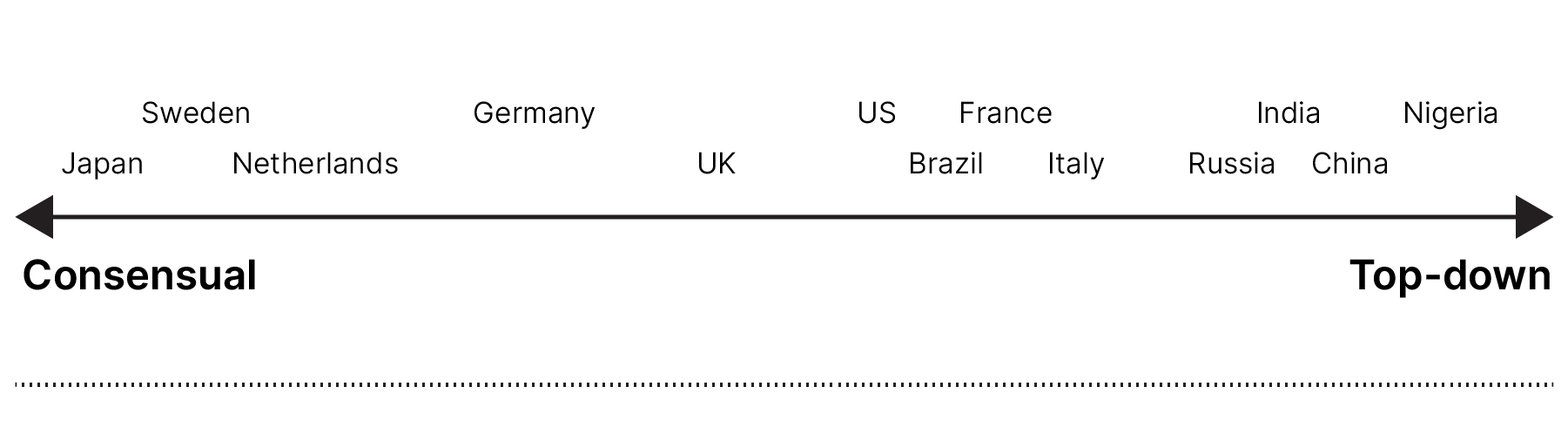

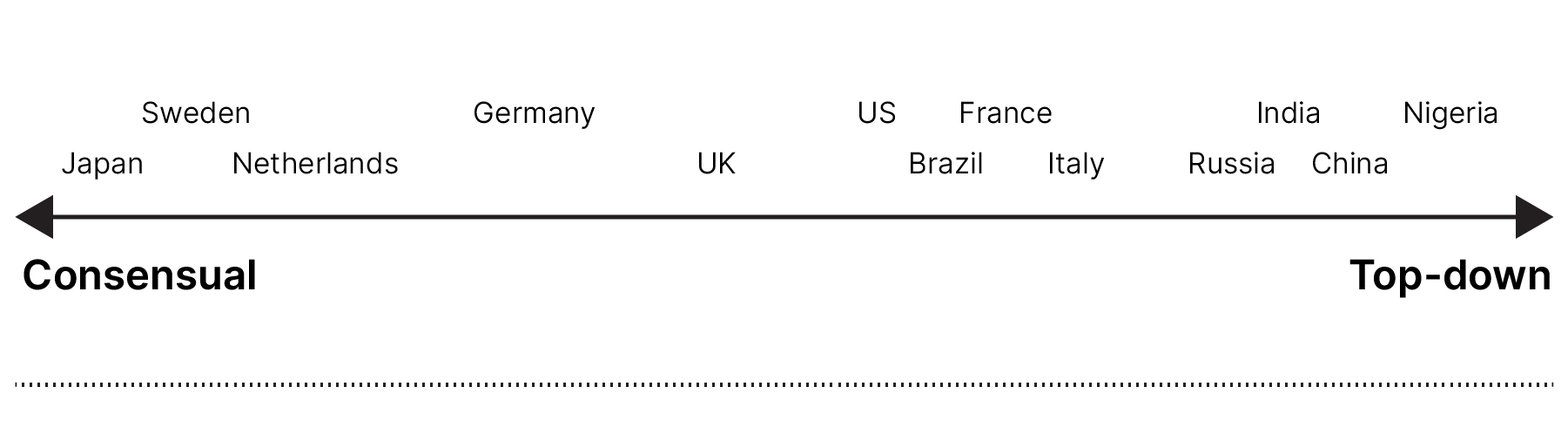

What impacts your decision making? This scale measures the degree to which a culture is consensus-minded. It can be quickly assumed that less hierarchical cultures will also be the most democratic, while the more hierarchical ones will allow the boss to make unilateral decisions — but this isn’t always the case. For example, Germans tend to follow more hierarchically structured ways, but are nevertheless more likely to build group agreement before making decisions.

In consensual cultures, decisions are made in groups through unanimous agreement.

In top-down cultures, decisions are made by individuals (usually the boss). Some cultures tend to question decisions after they have been taken, while others tend to discuss at length beforehand but stick to the consensus that was built.

--> As a team we acknowledge that discussing decisions after they have been taken or lengthily building consensus either way can mean long-tedious meetings and creating awareness around it was valuable.

Trusting

Source: “The Culture Map”, Public Affairs, 2014

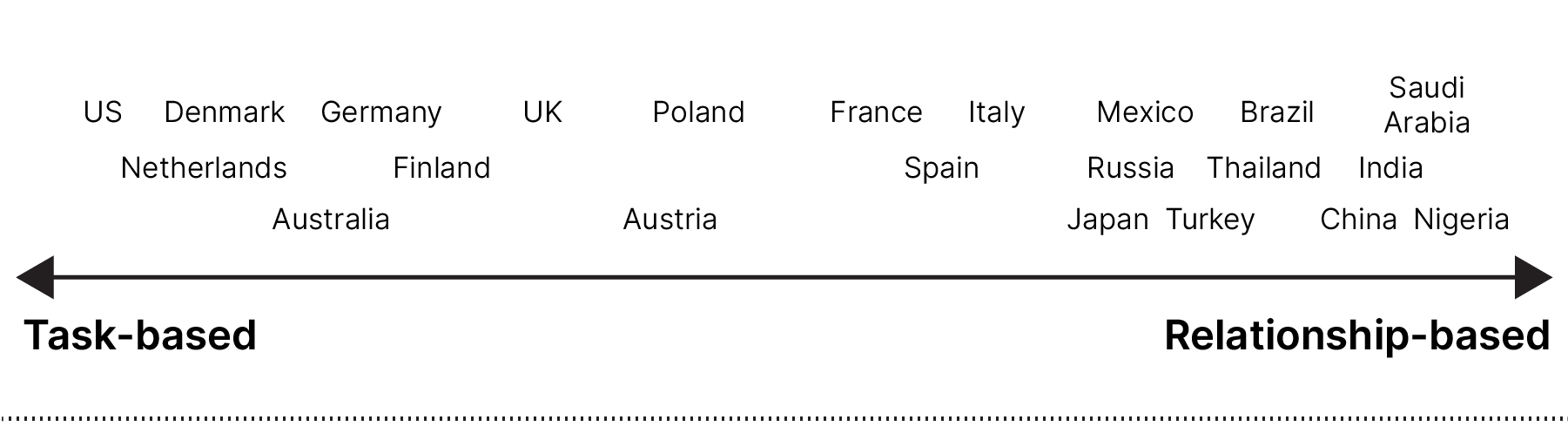

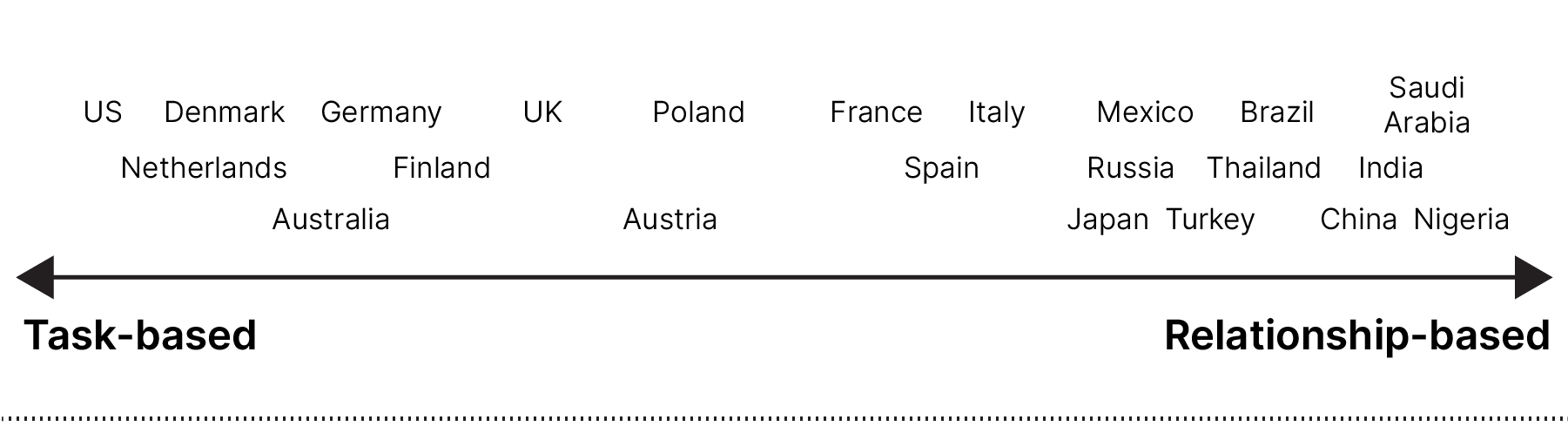

Do you trust with the head or with the heart? Cognitive trust (from the head) can be contrasted with affective trust (from the heart).

In task-based cultures, trust is built through work cognitively. If we collaborate well, prove ourselves reliable, and respect one another’s contributions, we come to feel mutual trust.

In a relationship-based society, trust is a result of creating an affective connection. If we spend time laughing and relaxing together, get to know one another on a personal level, and feel a mutual liking, then we establish trust.

--> Team members tending towards relationship-based trust building underlined the importance of regular, in-person meetings where possible. The opposite is true for team members who tend towards task-based trust, who shared how not having worked together made it more difficult to confidently engage in a debate with all colleagues alike.

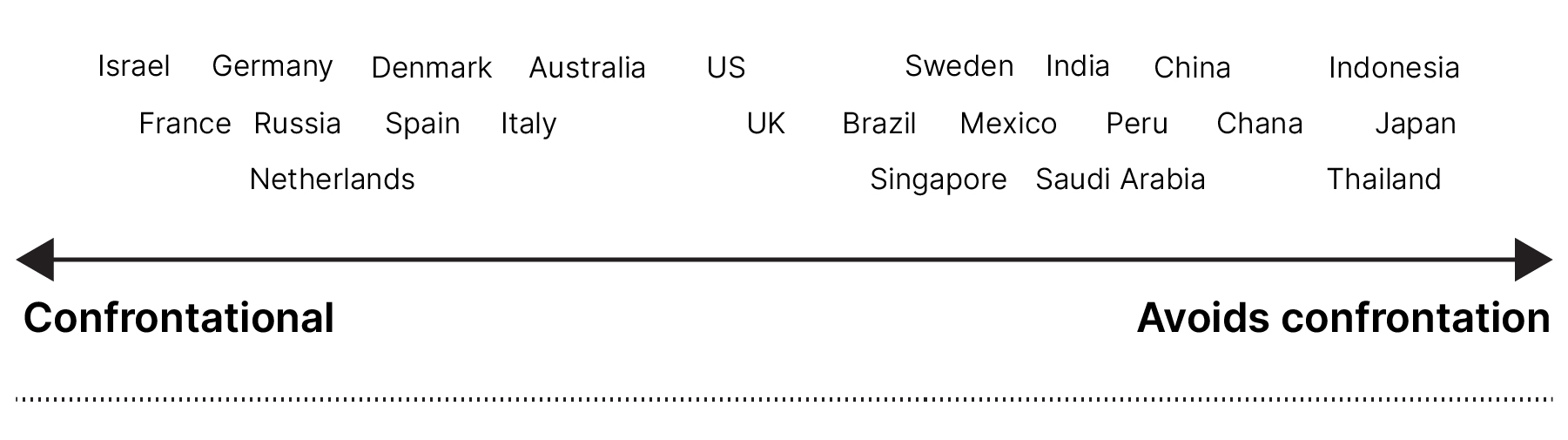

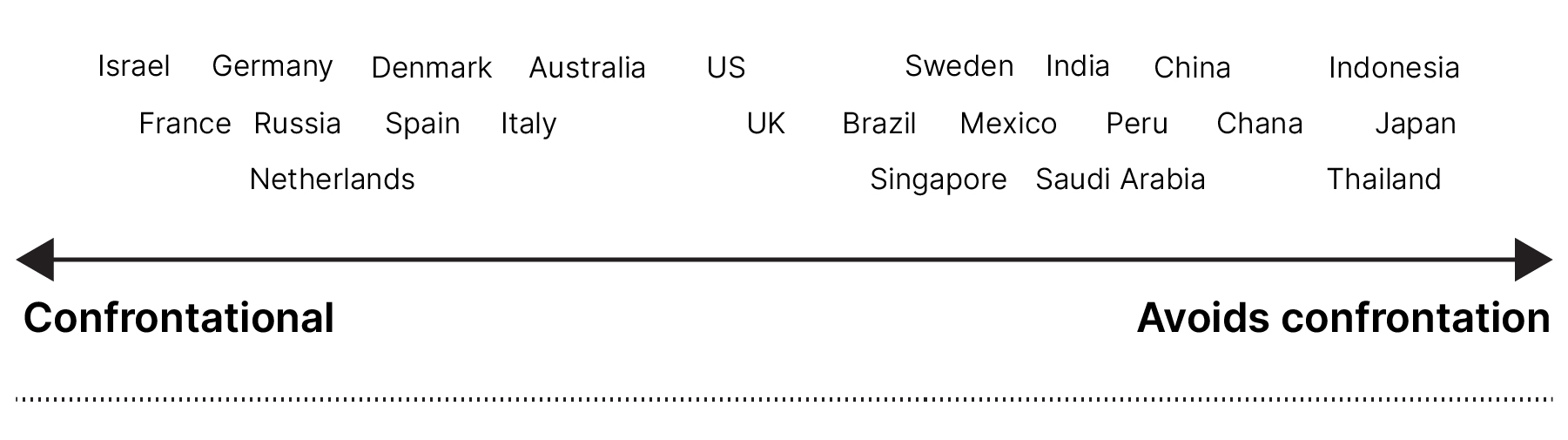

Disagreeing

Source: “The Culture Map”, Public Affairs, 2014

A little open disagreement is healthy, right? This scale measures tolerance for open confrontation and inclination to see it as either helpful or harmful to collegial relationships.

In confrontational cultures, disagreement and debate are regarded positively for the team or organization and will not negatively impact the relationship among team members.

In cultures that are more confrontation-avoidant, open confrontation is inappropriate and will break group harmony or negatively impact the relationship.

--> In our team we believe that a healthy debating culture supports robust decision making. It was valuable to see that not all team members enjoy a debate equally and ever since we strive for a more harmonious debating style.

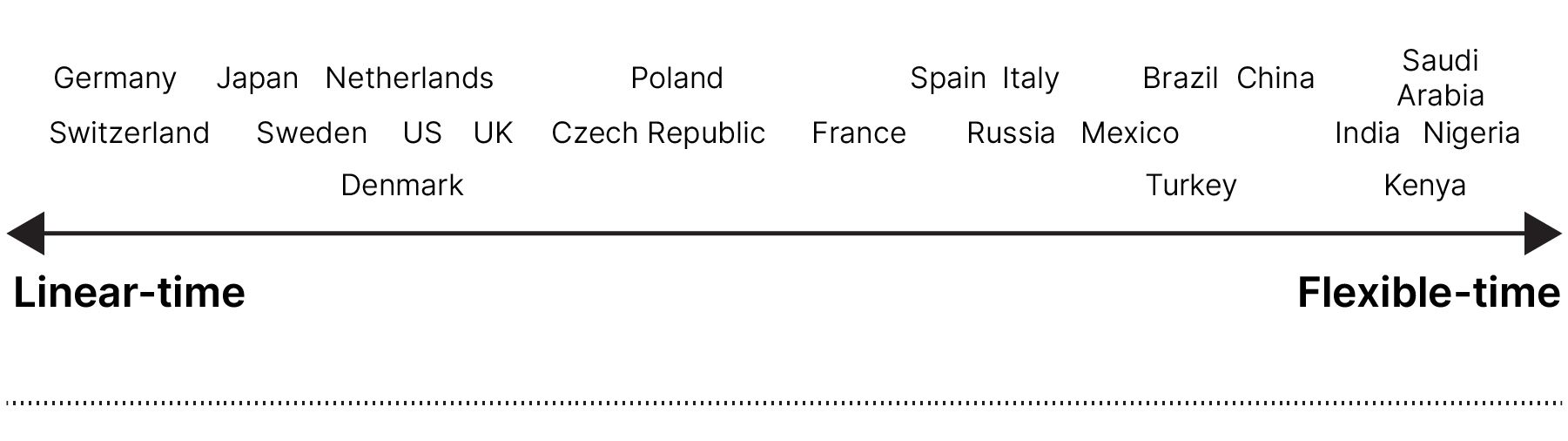

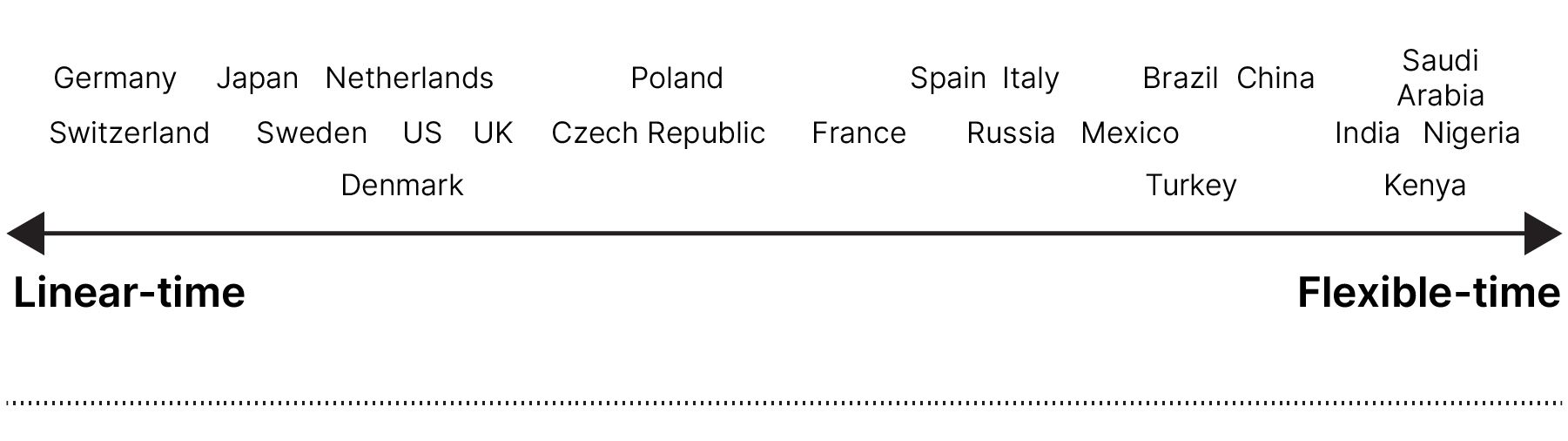

Scheduling

Source: “The Culture Map”, Public Affairs, 2014

How important is punctuality in reality? This scale assesses how much value is placed on operating in a structured, linear fashion versus being flexible and reactive.

In cultures tending towards the linear time perception project steps are approached in a sequential fashion, completing one task before beginning the next. The focus is on the deadline and sticking to the schedule. Emphasis is on promptness and good organization.

In cultures more inclined to flexible time perception, project steps are approached in a fluid manner, changing tasks as opportunities arise. Many things are dealt with at once and interruptions are accepted. The focus is on adaptability and flexibility.

--> It was revealing to discuss this in the light of the current times. The more uncertainty in a culture (or in a project), the more valuable a flexible handling of opportunities can be.

Take-aways from our experience

Knowing your own position in comparison to the default position of your home culture i.e. the culture you have been exposed to the most can unveil eye-opening insights. It can help transform an intuition or a spontaneous emotional reaction into an informed awareness based on which you can make decisions, for example about when to join or not join a discussion or how to structure conversations more consciously. As a team continues to work together, members can gradually develop a deeper understanding of each other's tendencies and preferences, enabling them to initiate open conversations, solicit feedback, and collaborate more effectively.

It is important to remember that there's no definite “best” position on the various scales. Trying to “fit into a certain box”, for example to match the position of a certain country, even if the whole team is located there, is counterproductive.

Nevertheless, it’s possible to give some clear advice: The more fluidly a person can move on the scale and react to one’s peers from various backgrounds, the higher the likelihood for successful international collaborations. If we are aware of the differences and know strategies for managing them effectively, each one of us will be much more likely to achieve our goals.