Open Banking: Designing for trust in consumer consent

In Australia, the Consumer Data Right (CDR) will go a long way in giving consumers trust, choice and control over sharing their personal data, but the CDR rules alone are only one part of the ecosystem. In the short term, it will be the role of financial institutions to implement the CDR through building a consent model to be used by their customers, partners and third parties.

During the course of our research, we discovered that many consumers share common feelings of skepticism, ambiguity and inertia around data sharing. We hope that the approaches discussed below will go some way in moving Australian consumers from passive to active data sharers, enabling the promise of Open Banking, and beyond to ‘Open Life’, a term that describes a future where consumers will have complete control of their data beyond banking to other open data verticals such as energy, telecommunications and even retail.

What is CDR and why should you care?

The Consumer Data Right was introduced by the government in August 2019 to provide Australians with the ability to share their personal data with businesses easily and securely in exchange for valued services. It aims to provide common data standards, with accredited third parties having the ability to access an individual’s data via application programming interfaces (APIs).

This new way of data sharing provides limitless opportunities for organizations to deliver richer, more personalised customer experiences than ever before. By accessing specific customer data, organizations can offer better deals and innovative products and services that are more relevant to consumer needs, convenient and highly secure, providing an incentive to switch.

What is consent?

In order to design a consent model we need to first understand what ‘consent’ means. In the context of the CDR, the Australian Competition and Consumer Commission (ACCC) outline that consumer consent must be “voluntary, express and informed and specific as to purpose, time limited and easily withdrawn”. However this is not how data sharing works in Australia today. The CDR aims to change this by giving consumers choice and control over their personal data, making them more informed than ever before.

Our research on data consent

CSIRO’s Data61 was appointed by the Australian Treasury as the Data Standards Body (DSB), to develop standards that will enable consumers to give consent to share and manage their data between parties. Thoughtworks, in partnership with advisory firm Greater Than X, supported the DSB in a Consumer Experience stream of work to design an online consent experience that takes into account the rules of the Consumer Data Right.

Our approach

The focus of our work was to design a consent model that will bring choice and control to data sharing and improve the propensity for consumers to share their personal data. During the initial phase of research, we sought to understand current attitudes and behaviours towards data sharing and what encourages or attracts people to be more active in sharing their personal data. We also studied how people think and feel about the new, proposed way of sharing and what needs to be provided in order to build trust and give consumers control when consenting to share personal information. We conducted customer interviews and presented a prototype that allowed participants to interact with a consent interface that encompassed the CDR rules.

The consent model we designed was tested with 20 participants across metro and regional areas, representing a sample of potential early adopters of the CDR. These initial insights were then used to inform a second round of design and testing that informed the final report for the Data Standards Body and their stakeholders. This final report supported a set of Consumer Experience Guidelines that we hope will build an ethical and transparent data sharing ecosystem for both consumers and organizations alike.

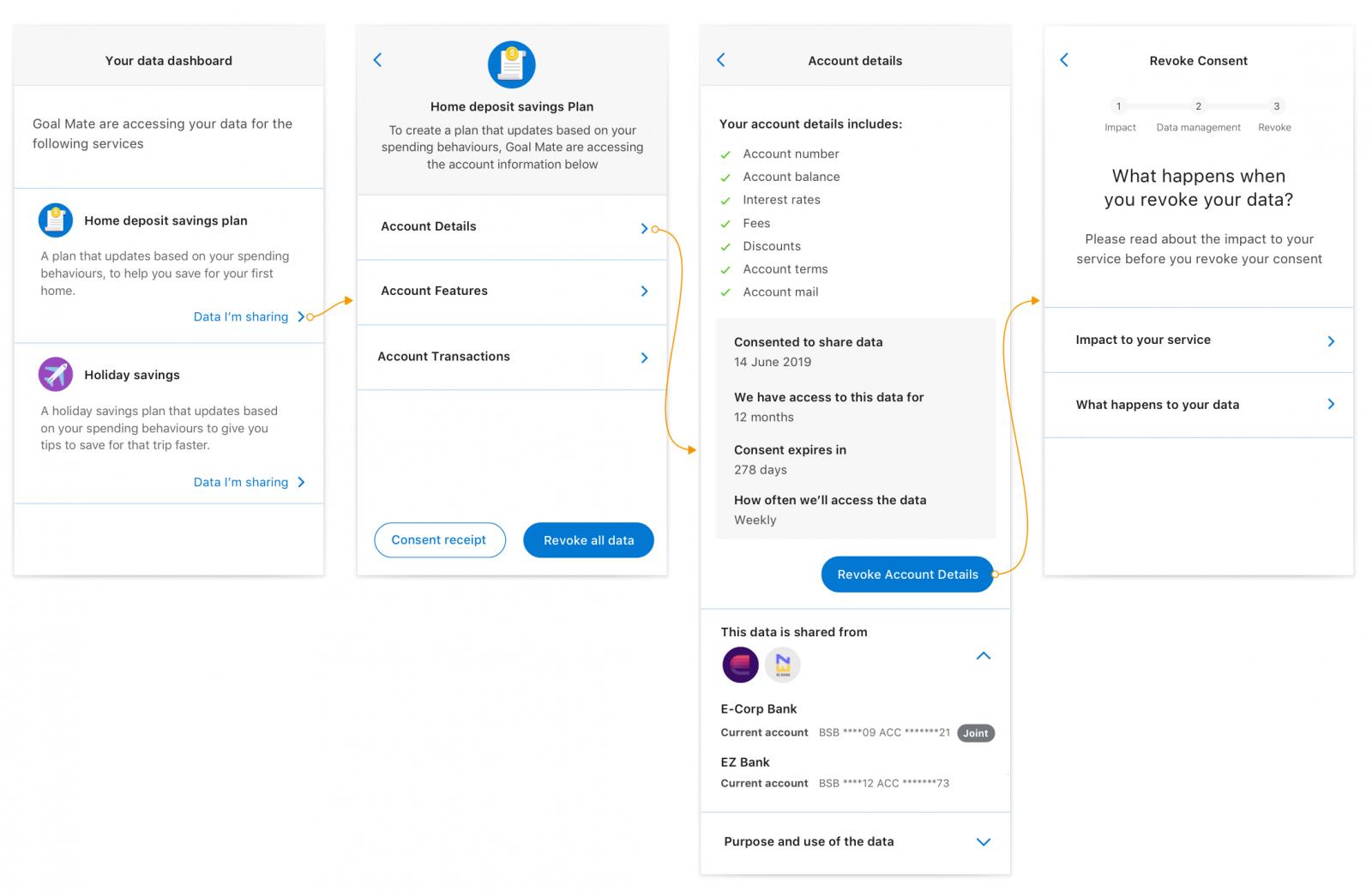

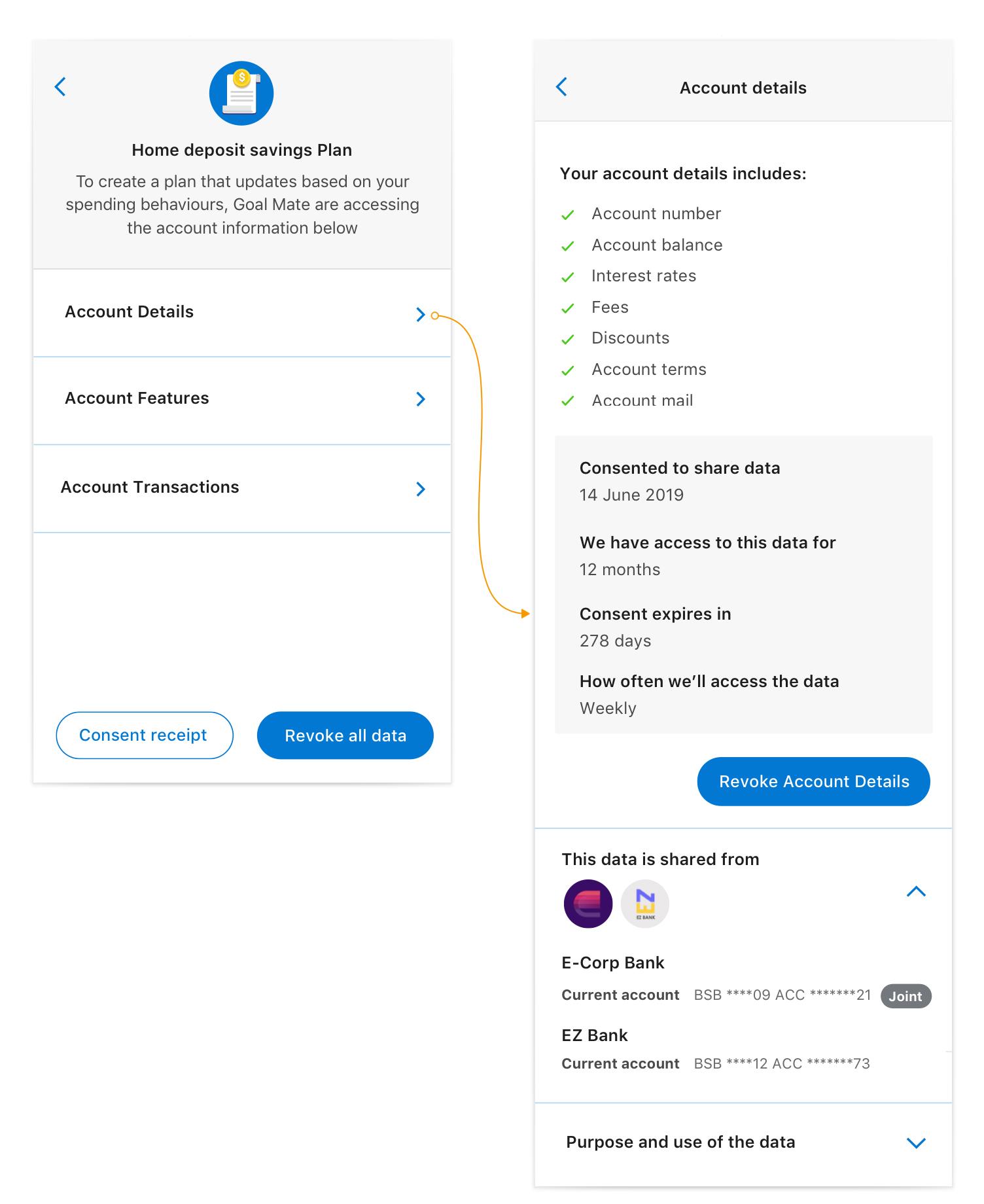

A sample of our final designs - this consumer dashboard shows the data that is being shared with a third party and the screen that is presented on withdrawal of consent.

Our findings

We found that in today’s information economy, personal information is shared so often that many no longer reflect on what they’re sharing. Much of this behaviour is driven by the passive acceptance that it’s simply “the way it is”. During the customer interviews, we asked participants how much control they feel they have when sharing their data today. Using a likert scale, 1 - being no control and 7 - complete control, the results showed an average of 3.

Those who gave low scores felt:

- It’s not explicit when and why data is being captured or how it’s being handled

- Once data is given, “it can’t be taken back”

- Terms and conditions may hold the information they need to be more informed, but many don’t want to read them

Those who gave higher scores felt:

- Laws and guidelines offer some comfort and rights to exercise control

- There are some existing mechanisms that help, such as social media settings and unsubscribe options

Participants expressed ‘security issues’ as a key motivator to stop sharing data. Many identified themselves or a friend/relative as being a victim of identity theft or a data breach and described previously taking action to immediately understand the impact, contact their bank and sometimes terminate their service through withdrawing consent or deleting the application from their device.

‘Value’ was seen as a key motivator for sharing. Participants expressed willingness to engage in data sharing when the value they perceive or are currently getting in return meets their expectations. This is key for organizations to acquire and hold onto consumer consent.

Designing for trust

Trust in this new data sharing ecosystem will be paramount. Consent models will add positive friction to the data sharing experience by explicitly outlining to consumers the data that they are about to share, how it will be used, and who will have access to it. Therefore the element of trust between a consumer and the organization will be the foundation on which consent is given or not. It will support the important shift consumers have to make from passive data sharing to active data sharing. It will be the challenge of those building consent models to alleviate as many negative trust factors as possible in order to increase the propensity for their customers to share their information with them.Designing a consent model

The second part of our research focused on the user interface (UI) of the consent model and understanding if the features, layout and language helped participants comprehend how this new way of data sharing will work and if they believe it provides them with choice, control and trust.

As stated in the CDR rules, consumers must be fully informed when consenting to share their data. Organizations must clearly state which data is being shared and the purpose for which the data is being used. We decided to utilise a progressive disclosure design pattern, which has been proven to focus the users attention by reducing clutter, confusion and cognitive overload. This meant each data cluster and its associated information was presented on a single screen. The consumer then had the choice to consent to that data cluster or not. We worked with the guiding principle that there should be no detriment to the consumer if they choose not to consent to share their data and we believe a basic level of product or service should be available regardless of their choice.

Progressive disclosure allows for each data cluster and it’s associated information to be presented on a single screen, one at a time. Please see the CDR CX Guidelines for latest recommendations.

The consent experience also provided up front information about how long the data would be accessed and the frequency at which the data would be collected, ensuring the consumer was fully informed before they made their decision to consent.

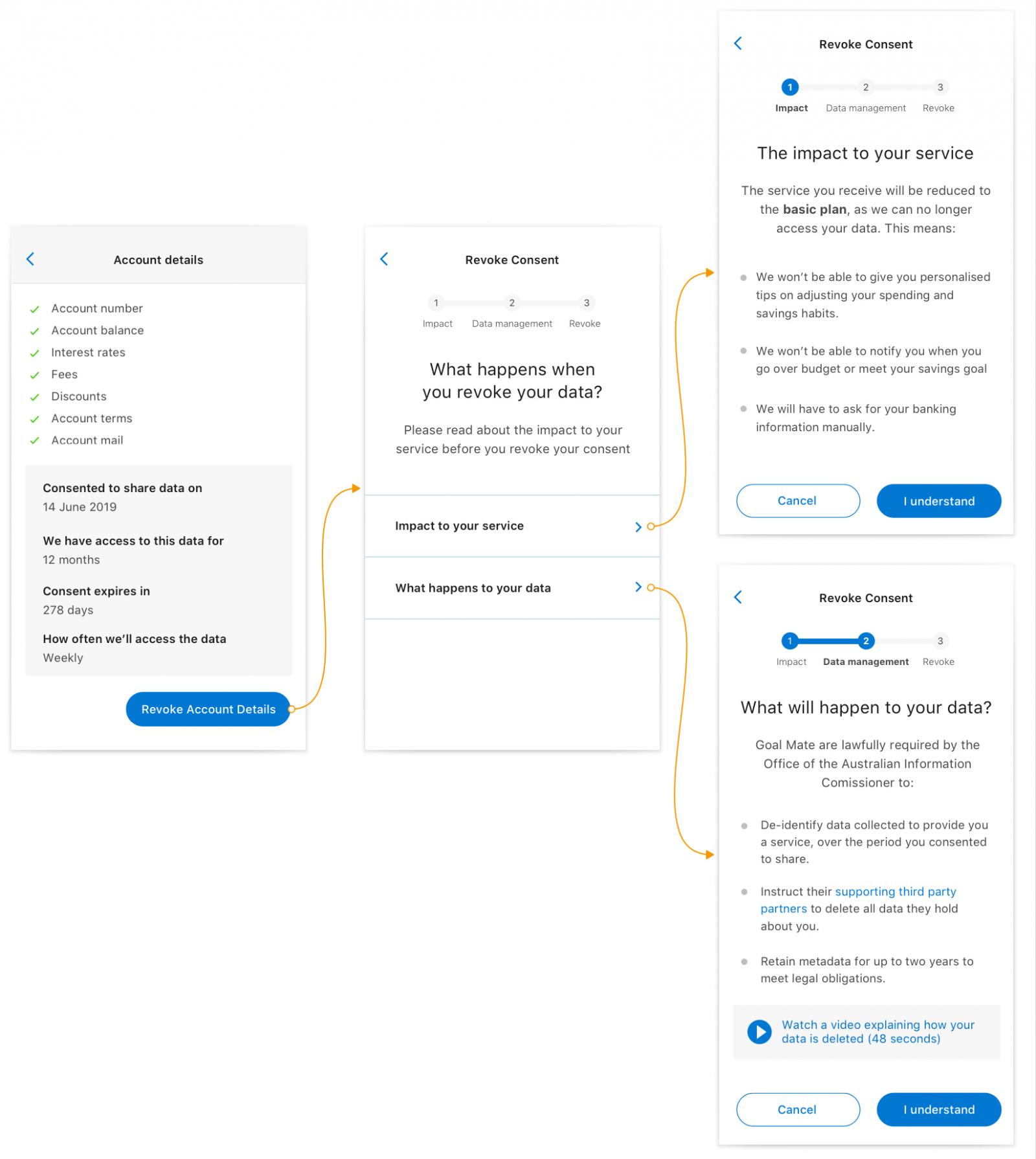

Withdrawing consent to share data, should also be fully informed. We believe consumers should be aware of the consequences of withdrawing, including the impact that it will have on their service, the specific data that they will no longer be sharing, the parties who no longer have access, and what will happen to their data. This transparency should leave participants with little concern from unanswered questions.

In round one of our research, we tested an assumption that including an ‘impact statement’ (i.e. a description of what may happen to a consumer’s service if their consent to data sharing is withdrawn) at the point of consent withdrawal would be sufficient to inform consumers of the consequences of no longer sharing their data. However we discovered that this statement alone was not enough and that consumers were still unclear on what happens to their data after they withdraw it, including data handling by supporting third parties. We addressed this by including a statement that explicitly outlines what happens to consumers’ data once it’s withdrawn.

We noted that whilst the data handling statement was now available, the way we structured the information on a single screen meant that information was competing with each other. Therefore, when we asked the participants to recall the consequences of withdrawing consent, their answers differed. To resolve this, we designed a third option that utilised the progressive disclosure pattern used in the consent flow, breaking down the ‘impact to your service’ and ‘what happens to your data’ into two distinct screens. Our assumption (which requires further testing) is that this will increase the consumers level of comprehension for both impact to service and data handling

Our third option broke down the ‘impact to your service’ and ‘what happens to your data’ into two distinct screens with the assumption it will increase comprehension of withdrawing consent. Please see the CDR CX Guidelines for latest recommendations.

Beyond withdrawing consent, most participants expected data to no longer be accessed, and any data stored by the accredited recipient to be deleted by them and their supporting parties. However there was skepticism as to whether the data is truly deleted and a lack of trust in organizations to do the right thing. The CDR gives explicit rules that data upon accreditation, suspension or withdrawal should be either de-identified or deleted. There is a need for transparency and clear articulation of how the organization chooses to handle the data, to instil greater trust in the process and ecosystem more broadly.

Under the CDR, accredited data recipients at a minimum must provide a CDR policy that includes any outsourced service providers e.g data processors, the nature of the service they provide and what CDR data is likely to be shared. It became clear during our research that it wasn’t obvious what relationship the outsourced service provider had with the accredited recipient. Participants felt uneasy at the idea that data could be carried across to an outsourced service provider and used against them to market unsolicited offerings. To alleviate these concerns we included an on-screen statement that clarified this relationship and how data will not be used for marketing purposes or any other reasons outside of the purpose statement of the CDR contract.

The road ahead

Beyond the consent model, financial institutions will need to build further trust by ensuring they deliver on the value they promise and provide consumers with transparency and greater assurance around security, in order to increase the propensity for them to share their personal information. The Treasury is currently developing a report into the future directions of the CDR and how it can further support a safe and efficient digital economy.

Financial services is only the first sector inline for the CDR with telecommunications and energy utilities up next, extending the possibilities of our consumer data rights and the control in which we can manage our Open Life.

Read more about the Consumer data right (CDR)

View the Consumer Experience: Standards and Guidelines

Disclaimer: The statements and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the positions of Thoughtworks.