UX - Are you Doing it Yet?

Over the past decade, User Experience Research and Design—often simply “UX”—has gained an increasingly prominent position in the world of tech. While the field has faced opposition within the industry, successful organizations are increasingly learning that investing in UX pay off.

Technology giants have large and diverse UX teams, and continue to grow them: Apple, Google, Facebook, and Amazon all hire UX researchers and designers out of top graduate programs worldwide. And their recruitment efforts offer a significant return on investment. UX isn’t just about design or about making things pretty—it’s about understanding your users or customers and finding product/market fit; it’s about learning what does and doesn’t work in your technology or business processes—as well as what doesn’t even exist yet, but should—and incorporating those findings into product development.

As Mitch Stein, who led a number of successful product releases at Apple, says:

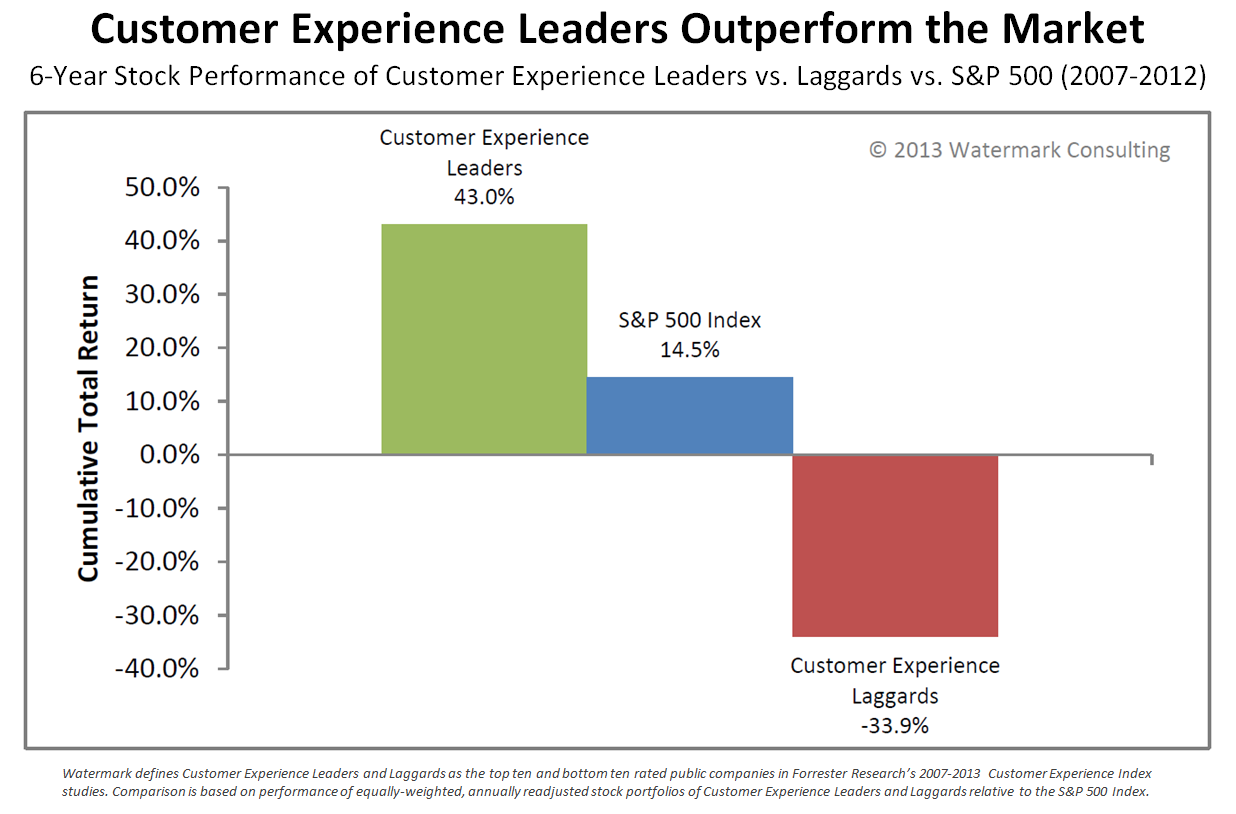

And it does really work—business schools everywhere are realizing the value of iterative design and research, and for good reason: companies offering positive customer experiences see dramatically higher performance relative to their peers. Watermark Consulting examined Forrester’s Customer Experience Index over a six year period and found that companies in the index’s top ten (“leaders”) outperformed those in the bottom ten (“laggards”) on the stock market by a wide margin.

Source: Watermark Consulting

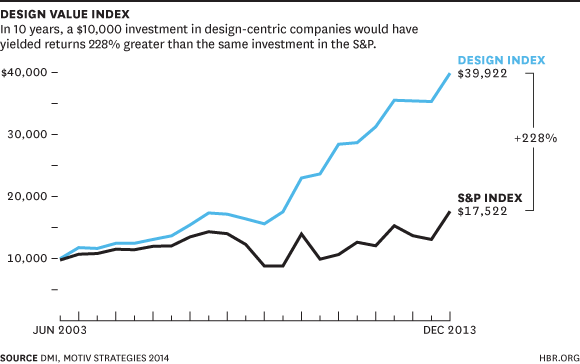

Similarly, Motiv Strategies and the Design Management Institute created a “Design Value Index,” an index of companies they deem to be design-driven. The results are similarly stark: last year’s index showed that design-driven companies outperformed the S&P 500 by 228% over the course of a decade.

Source: Harvard Business Review

Susan Weinschenk of Human Factors International has brilliantly laid out the business case for usability, pointing to a number of studies encouraging the use of UX to eliminate waste and save money in the software development process. She cites a well-known IEEE study on IT projects—and IT waste and failure in particular—and points out that “of the top 12 reasons that projects fail, three of the top 12 are directly related to what we would call user experience or user-centered design work, and those three are badly defined requirements; poor communication among customers, developers, and users; and stakeholder politics.” And while the figure she states is from an older study, Weinschenk highlights a compelling statistic to make the case for usability: including that every $1 invested in UCD returns between $2 and $100 (Pressman, 1992).

Even the US government has gotten on board with UX, encouraging organizations in government and industry to practice user-centered design in the hope of making usable technology a default. And lest anyone think UX is a frivolous or unnecessary expense, consider the fields of healthcare and air travel—two industries in which good or bad design can quite literally mean life-or-death. Dr. Bob Wachter recently published a book outlining the pros and cons of our increasingly digital healthcare system, and published a series of articles outlining just how poor system design—specifically, a lack of understanding of the hospital care context—led to the 38x drug overdose, and near-death, of a small boy in a hospital at UCSF.

Human Factors, a field that is in many ways the analog precursor to the digital era’s UX today, has long held a firm position in the design and development of aircraft. When people argue that healthcare should learn from the airline industry to improve patient safety in hospitals nationwide, much of what they’re talking about is the robust system of human factors / UX engineering that has been embedded in the aviation industry for years. Even Atul Gawande’s best-selling Checklist Manifesto is largely about the ideas that easily boil down to UX: understand the workflows, processes, and other behaviors of your users in their environments, and design a solution to be used successfully by them in that context.

It’s a basic truth: successful organizations emphasize and invest in UX, integrating it into their teams alongside product and engineering. Can yours afford not to?

A common excuse used by organizations not doing UX is that they lack the resources to make it a reality: money, time, or expertise, among others. But the above business cases show that UX is, or at least should be, a necessity, a given, among organizations of any size. Do you have a product of some kind? Do you have customers who use that product? Then you should probably have some sort of UX—whether that’s customer experience, experience design, user research, or any other permutation of the name—to understand both, and the intersection of the two.

Businesses have long recognized the need for certain skill sets in order to run a successful organization—accounting, business analysis, marketing, product management and engineering for tech companies—and yet UX consistently seems to be left out in the dark, despite mounting research that it should be placed in esteem alongside all these other roles. An estimated 70% of technology projects fail due to a lack of user adoption: shouldn’t you understand your users and product as much as possible in order to prevent this from happening?

Some, however, are starting to pay attention—including forward-thinking organizations and graduate programs, among others. CNN Money recently listed UX Designer at #14 of its top 100 jobs this year, and others are beginning to notice a dramatic increase in opportunities for professionals in the field, with no signs of slowing, and a growing number of universities are offering graduate programs leading to UX careers.

Clearly, UX is happening somewhere.

Finding Hidden Opportunity

When many think of UX, they think of design, slick user interfaces, and maybe usability testingthey think, in other words, of honing the final design of an established product. But the field is much broader than this, and seeks to provide much more fundamental value than just those things.

Qualitative research—especially interviews and ethnography—is a lesser-known venue for gaining user feedback that can pay off throughout the product development lifecycle. This includes especially helping organizations to learn “what to build” in the first place as they discover strategies for product/market fit, monetization and user acquisition models, and more. Conducting early-stage ethnography and interviews can provide a wealth of information about customer personalities, contexts, behaviors, and wants and needs, and all of this can help inform future product decisions around not only how to design and build something, but what to build in the first place.

The idea of conducting this kind of research may sound radical, but it shouldn’t: Procter & Gamble have been sending managers and senior leaders out into the field to conduct “immersion research” for years. This may include spending a week or more living in low-income homes and shops, and has helped to shape product direction significantly. P&G call their program “Living It” and never refer to the methodologies as UX per se, but the methods and goals of the processes are identical: to “get out of the building” to better understand users while developing products intended for their use.

Similarly, Gregg Bernstein and his user research team at MailChimp have learned about opportunities for entirely new products as a result of proactive qualitative research. Bernstein describes how the idea for MailChimp Snap came not from a desire to research a new product, but rather from a practice of conducting early stage exploratory research: “we research people and we try to better understand what would make them happy, what would fit into their lifestyle, what would fit into their day-to-day. We don’t go out with an idea for a product in mind.”

Qualitative UX research can provide a great opportunity to learn more about customers, and learn how current and developing products can be shaped, modified, or perhaps even invented altogether to fit into their lives.

Validating Findings - Quantitative Measurement

Qualitative research can, and should, be conducted hand-in-hand with quantitative. Qualitative research is great at answering questions like why and how and helps the researcher learn what she should be measuring. Quantitative research, meanwhile, is able to do the measuring of whatever it is that’s been decided to measure; it is much better at precisely telling us what happens when and how often.

Many researchers advocate for a mixed-methods approach tying in both qualitative and quantitative research, allowing the findings from each to support those of the other. When seeking the quantify the voice of the user—around her use of a mobile app, for instance—a number of quantitative methods can be employed. Among them:

Surveys

While surveys can be used to gather both qualitative and quantitative data, they are particularly useful for gaining feedback from relatively large numbers of individuals. Surveys might ask users about their use of a product or system, or some other behavior or details about user lifestyles that may be relevant in some other way.

A/B Testing

A fundamental aspect of UX—and Lean/Agile methodologies in general—is the idea of rapidly testing—and then rejecting, pivoting, or continuing to press on with ideas. A/B testing allows this to happen in a relatively rigorous, easy manner, and can provide a lens through which to view user behavior without needing to ask (and potentially, bias) them.

Usability Testing

Usability testing can be both qualitative and quantitative in nature, but, as with surveys and A/B testing, generally only occurs once a product has arrived at some sort of coherent state in the form of a Minimum Viable Product (or MVP). Once the product is in a state in which it can be used, and its use observed - even if that use involves, for instance, low fidelity paper prototypes—then users can be tasked with scenarios for working through a system, and its use observed from a neutral point of view. Usability tests can be conducted using prototypes and functioning products at all stages of development, from lo-fi paper prototypes, to interactive prototypes which can be developed using a wide array of prototyping tools, to Wizard-of-Oz studies that can involve someone from the UX team manually manipulating some part of the prototype to make it feel as though it’s functional software, up to full software prototypes that can be run and tested as functional software. Usability tests can be especially helpful for learning what users expect out of a system, as well as pain points and opportunities within the existing product.

And of course, still other, more exotic UX methodologies—such as leading users through a participatory design workshop to facilitate their design of parts of a product themselves—can be explored to add additional value as well. The list is nearly endless.

Bit by Bit, the Field Grows

While this list of UX methods may seem daunting, they needn’t all be deployed at once, or even at all. A major advantage of the way in which these methods has been laid out - from qualitative to quantitative, from relatively low effort (interviews, observations and ethnographies) to much higher effort (surveys, A/B tests and usability tests) is that many informational gains can be obtained early on.

While a variety of methods for gaining user feedback is ideal, even a little is infinitely better than nothing at all. Individuals on software development teams may often be surprised by how much they can learn through a brief conversation with a customer or three. Ideally, the seeds of a UX process lead to small successes that help UX to grow—this growth can lead to further reinvestment in UX as the process comes to be seen as a not only valuable, but even necessary set of roles within a company.

While UX as a profession is gaining traction—more and more companies are realizing the value of design and customer centricity, and ever more graduate schools and undergraduate universities are springing up nationwide—it can be hoped that one day the UX professional will find herself comfortably at home within any organization.

This article was originally published as part of the series “Design And Technology: Joining Forces For A Truly Competitive Advantage content on InfoQ”.

Disclaimer: The statements and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the positions of Thoughtworks.